Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Eric G. Lambert Department of Criminal Justice The University of Toledo

Nancy Lynne Hogan School of Criminal Justice

Ferris State University

Shannon M. Barton Department of Criminology

Indiana State University

Academic dishonesty is a serious concern on most college campuses as it cuts to the heart of the purpose of higher education and the pursuit of knowledge. This study examined twenty different types of academic dishonesty as well as potential correlates of academic cheating by surveying 850 students at a four-year Midwestern university. While most past studies have used bivariate analysis, this study expands the literature by also including a multi-variate analysis to determine which correlates were most important in accounting for collegiate academic dishonesty. The results indicated that most of the bivariate associations were not observed in the Ordinary Least Squares analysis, suggesting that after controlling for shared effects, many variables have little overall effect on the summed measure of academic dishonesty. Specifically, only college level, membership to a fraternity or sorority, cheating to graduate, cheating to get a better grade, and past cheating in high school had a significant impact.

From the literature, it appears that academic dishonesty is epidemic across most college campuses, and the majority of students have engaged in it to some degree at some point in their academic careers (Baird, 1980; Davis, Grover, Becker, & McGregor, 1992; Eskridge & Ames, 1993). Documented since at least the 1920s (e.g., Brownell, 1928) and an ongoing concern for the past 80 years (McCabe & Bowers, 1994; McCabe & Trevino, 1996; Spiller & Crown, 1995), research on the subject has intensified during the last two decades (Diekhoff, LaBeff, Clark, Williams, Francis, & Haines, 1996). Academic dishonesty, a serious concern on most college campuses, cuts to the heart of the purpose of higher education. The finished products of the university, its students, may not possess the fundamental information and skills implied by the transcript. Academic dishonesty is an affront to academically honest students as well as most college professors whose purpose is to teach.

Most of those employed in higher education do not condone cheating and view academic dishonesty as a serious problem that needs to be addressed. In order to effectively combat cheating, it is necessary to understand how it is done, who does it, its forms, and why it is done.

This study attempts to broaden the understanding of academic dishonesty in two ways. First, most previous studies have focused on a narrow range of cheating behaviors. This study asked students about 20 different types of academic dishonesty. Second, this study attempted to reveal which correlates were the strongest predictors of academic dishonesty with multi-variate analysis. Correlates from past research were included in the multi-variate analysis. It is important to note that this is an atheoretical study. While no particular theory is utilized to explain academic dishonesty among college students, the results are nevertheless important. Identifying important correlates of academic dishonesty should help provide a better picture of past findings and also allow those interested in curbing cheating to focus upon important predictors of academic dishonesty.

Academic dishonesty is difficult to define precisely. Kibler (1993, p. 253) contended, “One of the significant problems a review of the research literature on academic dishonesty reveals is the absence of a generally accepted definition.” Some definitions include the intentions of the person engaging in the dishonest behavior (e.g., Tibbetts, 1998, 1999). For example, Von Dran, Callahan, & Taylor (2001, p. 40) wrote that academic dishonesty “is defined in the literature as intentionally unethical behavior.” Other studies defined academic dishonesty based upon a particular violation behavior, such as cheating on a test or plagiarism (e.g., McCabe & Bowers, 1994; McCabe & Trevino, 1993). Some behavioral-based definitions are even more general. For example, Weaver, Davis, Look, Buzzanga, and Neal (1991, p. 302) defined academic dishonesty as “a violation of an institution’s policy on honesty.” In this paper, academic dishonesty was broadly defined as any fraudulent actions or attempts by a student to use unauthorized or unacceptable means in any academic work. This definition is similar to that used by Pavela, (1978, 1997) and Blankenship and Whitley (2000). Lastly, there is the issue of terminology. Frequently the terms academic dishonesty and cheating are used in the literature (Whitley, 1998). While there may be subtle differences, for the most part these terms represent the same concept, and in this paper are used interchangeably.

From a review of the literature, there are many different forms of academic dishonesty (Caruana, Ramaseshan, & Ewing, 2000; Coston & Jenks, 1998; Kibler, 1993; McCabe & Trevino, 1993; Roig & DeTommaso, 1995; Stern & Havlicek, 1986). According to Pavela (1978), there are four general areas that comprise academic dishonesty: 1) cheating by using unauthorized materials on any academic activity, such as an assignment, test, etc.; 2) fabrication of information, references, or results; 3) plagiarism; and 4) helping other students engage in academic dishonesty (i.e., facilitating), such as allowing other students to copy their work, maintaining test banks, memorizing questions on a quiz, etc. Student academic dishonesty includes, but is not limited to, lying, cheating on exams, copying or using other people’s work without permission, altering or forging documents, buying papers, plagiarism, purposely not following the rules, altering research results, providing false excuses for missed tests and assignments, making up sources, and so on (Arent, 1991; Moore, 1988; Packer, 1990; Pratt & McLaughlin, 1989). In this study, a wide range of forms of academic dishonesty were measured.

The number of students who admit cheating (i.e., prevalence) has received considerable attention in the literature. In a survey of marketing students, it was found that 49% admitted to some form of cheating (Tom & Borin, 1988). In an anonymous survey of students at a major university, over two-thirds reported cheating at least once (Hollinger & Lanza-Kaduce, 1996). In a survey sent to more than 15,000 students at 31 major universities, it was found that over 60% admitted cheating at least once (Meade, 1992). Most studies estimated that 50% to 65% of college students engage in some form of academic dishonesty (Davis et al., 1992; Gardner, Roper, Gonzalez, & Simpson, 1988; Haines, Kiefhoff, LaBeff, & Clark, 1986; Jendrek, 1992; LaBeff, Clark, Haines, & Diekhoff, 1990; McCabe, 1992). Still other studies have found a higher rate (i.e., 70% or more) of students admitting they have engaged in some form of academic dishonesty (e.g., Eskridge & Ames, 1993; Genereux & McLeod, 1995; McCabe and Bowers, 1994). In a meta-analysis, the mean prevalence of cheating was 70% (Whitley, 1998).

It appears that there is significant variation in the total number of students who admit to cheating. This is largely due to three factors. First, when measuring the overall rate of academic dishonesty, time frames matter. Some studies only asked about behavior during the prior six months (e.g., LaBeff et al., 1990), while others ask if the student had ever cheated while in college (e.g., Coston & Jenks, 1998). Second, studies have defined and measured academic dishonesty differently. Some studies asked students about a very limited range of academic dishonesty, such as cheating on a test or plagiarism. Other studies asked students about a much wider range of academic dishonest behaviors, such as altering test results, cheating on homework assignments, buying papers, and so forth. Since a common base was not used, it is not surprising that varying results were observed. Third, colleges differ in their rates of academic dishonesty because no two colleges are the same in terms of their student bodies and their collegiate environment. This observation lead to many studies that examined which students engage in academic dishonesty.

In order to determine who cheats, correlates of academic dishonesty have been studied. One area of correlates to receive a great deal of attention has been the demographic characteristics of students who cheat and those who do not (Haines et al., 1986; Stevens & Stevens, 1987). Gender has been often linked to academic dishonesty, with men generally reporting a higher level than women (Aiken, 1991; Genereux & McLeod, 1995; McCabe & Trevino, 1997; Michaels & Miethe, 1989; Newstead, Franklin, Stokes, & Armstead, 1996; Ward, 1986; Whitley, 1998), but not always (Coston & Jenks, 1998; Haines et al., 1986; Houston, 1983; Jordan, 2001; Stevens & Stevens, 1987). Sex-role socialization is typically provided to explain the difference in cheating (Ward and Beck, 1990). It is argued that women are socialized differently and view cheating more more negatively.

Age has been negatively linked to cheating in college, with younger students cheating more frequently than older students (Antion & Michael, 1983; Diekhoff et al., 1996; Haines et al., 1986; McCabe & Trevino, 1997; Newstead et al., 1996; Whitley, 1998), but not always (Hilbert, 1985; Tang & Zuo, 1997). The argument is that younger students are more immature in terms of both age and personality (Haines et al., 1986). Marital status has also been associated with academic dishonesty, with married students being lower in their level of academic dishonesty (Diekhoff et al., 1996; Haines et al., 1986; Whitley, 1998). The literature is unclear about why. It is possible that married students have a different perspective on life or are more mature. Additionally, age probably played a significant factor in this inverse association, since married college students tend to be older than single college students.

Aside from demographics, studies have looked at other personal characteristics. There appears to be no relationship between the strength of a student’s superego and cheating (Whitley, 1998). Academic dishonesty does not seem to be linked with authoritarianism (Whitley, 1998). On the other hand, religious values have been found to decrease student cheating (McNichols & Zimmerer, 1985; Smith, Wheeler, & Diener, 1975; Sutton & Huba, 1995), but this has not always found to be the case (Whitley, 1998). Furthermore, the stage of moral development has been found to be correlated with academic dishonesty (Diekhoff et al., 1996; Micheals & Miethe, 1989), but it was not a strong correlation (Lanza-Kaduce & Klug, 1986; Whitley, 1998).

College characteristics have also been examined. College level (i.e., freshman, sophomore, etc.) has been linked to cheating (Jordan, 2001; Michaels & Miethe, 1989), but not always (Whitley, 1998). Among the studies in which a relationship was found, it is unclear which level cheated more.

Grade point average (GPA) has been associated with academic dishonesty, with students in the lower ranges more likely to have cheated than students with high GPA’s (Antion & Michael, 1983; Bunn, Caudill, & Gropper, 1992; Diekhoff et al., 1996; Genereux & McLeod, 1995; Haines et al., 1986; McCabe & Trevino, 1997; Scheers & Dayton, 1987; Whitley, 1998), but not always (Jordan, 2001). The rationale for this relationship is that those with lower GPA’s have less to lose and more to gain by engaging in academic dishonesty (Leming, 1980; McCabe and Trevino, 1997). In addition, it is possible that those with lower GPAs may have poorer academic skills, which may cause them to feel that they must cheat.

Involvement in extracurricular activities has been linked to increased cheating. Those involved in sports have, on average, higher levels of academic dishonesty as compared to students who are not involved with a varsity sport (Diekhoff et al., 1996; Haines et al., 1986). Additionally, fraternity and sorority membership has been linked to higher rates of cheating (Baird, 1980; Diekhoff et al., 1996; Haines et al., 1986; Kirkvliet, 1994; McCabe & Trevino, 1997; Whitley, 1998). One theory is that there may be social pressures from the groups involved in extracurricular activities that support academic dishonesty. Further, students involved in extracurricular activities have less time to devote to academics and have less time to devote to studying (McCabe & Trevino, 1997). On the other hand, employment has been observed to be inversely correlated with cheating (Diekhoff et al., 1996; Whitley, 1998). This contradictory finding with employment provides support for the social pressure theory rather than the lack of time theory, since employment also decreases the amount of time available to devote to academics.

Finally, area of study or major has been found to be important (Tibbetts, 1998), but not always (Jordan, 2001). However, in general, the literature suggests that cheating is relatively consistent across most disciplines. For example, Coleman and Mahaffey (2000) found business majors were similar in their views of cheating as compared to students in other programs. Other studies have found no difference in levels or types of cheating between criminal justice and other majors (Eskridge & Ames, 1993; Tibbetts, 1998).

Various rationales for cheating have been tested as well. It is argued that cheating can be deterred by the threat of official sanctions. Fear of being caught should reduce the amount of academic dishonesty (Diekhoff, LaBeff, Shinohara, & Yasukawa, 1999; McCabe & Trevino, 1997). In one study, the perception of being caught was found to be inversely related to cheating (McCabe, Trevino, & Butterfield, 2001). On the other hand, some studies suggest that formal sanctions have little effect, and that informal sanctions by students peers matter more. For example, Cochran, Chamlin, Wood, and Sellers (1999) found that perceived shame of being caught had a significant impact on five different forms of cheating by 448 students at the University of Oklahoma, but found no impact for the threat of formal sanctions. In a study of 330 students at a mid-Atlantic public university, Tibbets (1998) and Tibbetts and Myers (1999) found that moral beliefs and shame were significant predictors of intention to cheat on a test in a hypothetical scenario, but low-self control had no effect. Conversely, Cochran, Wood, Sellers, Wilkerson, and Chamlin (1998) found that low self-control also accounted for some of the self-reported academic dishonesty among students at the University of Oklahoma. In general the literature supports the postulation that moral beliefs have a strong impact on whether a person engages in academic dishonesty. Specifically, the belief that cheating in any form is wrong has been inversely linked to academic dishonesty (Tibbetts, 1998; Tibbetts & Myers, 1999). Conversely, those who have weak moral views on cheating were more likely to engage in various forms of academic dishonesty (Whitley, 1998).

The literature also suggests that alienation may cause students to engage in academic dishonesty (Eve & Bromley, 1981; Newhouse, 1982). Similarly, a small but statistically significant association between anomie (i.e., lack of being tied to society and norms) and cheating was observed among business majors at an Australian university (Caruana et al., 2000). Cheating may also occur because of low levels of commitment to the ideals of higher education and learning orientations (i.e., wanting to learn versus earning a grade/degree) (Haines et al., 1986; Weiss, Gilbert, Giordano, & Davis, 1993; Whitley, 1998). Talking with students about the subject of academic dishonesty and ethics can lead to a decrease in cheating (Kibler, 1993). Finally, past behavior tends to be the best predicator of future behavior, and this appears to be true for academic dishonesty. It was observed that those who cheated in high school are more likely to cheat in college (Whitley, 1998).

The issue of situational ethics has been discussed frequently in the academic dishonesty literature. Many students argued that cheating is not universally wrong (LaBeff et al., 1990). Under certain circumstances some students felt that cheating can be justified (LaBeff et al., 1990). This may explain why most cheaters try to justify their behavior (Haines et al., 1986; Roig & Ballew, 1994; Whitley, 1998). The justification of cheating is based upon the concept of neutralization proposed by Sykes and Matza (1959). The higher the expected reward, the higher the rate of cheating (Whitley, 1998).

A frequently provided reason for being dishonest in college has been the appeal to higher loyalties (Genereux & McLeod, 1995; LaBeff et al., 1990; Lanza-Kaduce & Klug, 1986; McCabe, 1992). The appeal to higher loyalties was generally from their friends and colleagues in extracurricular activities, such as sports or fraternities/sororities. Similarly, McCabe & Trevino (1997) found that peer disapproval was a significant predicator for not cheating. Other reasons for cheating were the desire to receive good grades (McCabe, 1992; Singhal, 1982) or the need to keep a scholarship (Diekhoff et al., 1996). The need to get a good grade was frequently linked to engaging in academic dishonesty (Coston & Jenks, 1998; Genereux & McLeod, 1995; Robinson, & Kuin, 1999; Whitley, 1998). Additionally, cheating was sometimes argued to be justified because of the course is too hard or the instructor is unfair (Coston & Jenkins, 1998; Diekhoff et al., 1996). Furthermore, the justification of the need to be admitted to a particular graduate/professional school has been found to be correlated to cheating (McCabe, 1992).

In summary, many students, across a wide array of colleges and majors, appear to cheat. The literature further reports that many students try to justify engaging in different forms of academic dishonesty for a variety of reasons, such as competitiveness of their major, course difficulty, the need for professional success, cynicism, and that other students cheat (Chop & Silva, 1991; Davis, 1992; Fass, 1986; Mixon, 1996; Simpson, 1989). While there has been significant research on the subject of academic dishonesty, why students cheat and what types of cheating they typically engage in and has not been fully answered. As Caruana et al., (2000, p. 23) contend, “Little research appears to have been done to try and identify variables that have an effect on academic dishonesty.”

While a significant amount of research has been done on academic dishonesty, there is still a need for further research. Many studies examined only a narrow range of cheating behaviors. Additionally, while there is a growing body of correlates to college cheating, the question becomes which are the best predictors. Most potential antecedents or correlates of academic cheating have only been examined a handful of times. Moreover, most of research on subject has been correlational or bivariate (Whitley, 1998). Very few studies have used multi-variate analysis to determine which of the correlates were the strongest predictors of frequency of academic dishonesty. Multi-variate analysis helps to determine the impact of independent variables on the dependent variable once shared effects are taken into account. In this study, personal characteristics, fear of being caught, religious views, and other measures were entered into a multi-variate analysis with a composite measure of total times of cheating is the dependent variable. As Whitley (1998, p. 265) points out, “effective interventions can be designed only when the causes of an undesirable behavior are known.” The results of the multi-variate analysis should shed some light on which correlates might be important in accounting for collegiate academic dishonesty.

As previously mentioned in the introduction, this is an atheoretical study. No particular theory was tested. Rather, correlates from past research were included in the multi-variate analysis to see which were significant predictors of academic dishonesty. While this research does not study a particular theory to explain academic dishonesty among college students, the results nonetheless should be important. By using multi-variate analysis, it is argued that significant correlates may be uncovered, which should help provide a better picture of past findings and provide those interested in curbing cheating important correlates and factors to focus upon.

In researching academic dishonesty, surveys were the most common method used (Whitley, 1998). The data for this study was drawn from a survey of college students at a four-year public university in Michigan, with a total enrollment of about 10,000. A non-random, convenience sampling design involving more than three dozen academic courses in the Fall of 1999 was utilized (Hagan, 1997). Students were asked to participate in the study by voluntarily completing a survey during class time. The class sizes ranged between 15 and 50 students. A mixture of classes was selected, including general education courses. Because general education courses are required as part of the university’s requirements for students pursuing a four-year degree, the sample contained a wide variety of majors.

All students were told not to complete the survey if they had previously completed one in another course to prevent double participation by students. While no student was required to participate and all were told that they could decline participation without penalty, more than 95% of the students completed the survey. A total of 850 useable surveys was completed and returned. The demographic characteristics of the respondents are presented in Table 1. In general, the demographic characteristics were similar to the overall student population. For example 79% of the student body was White and 83% of the respondents were White. Additionally, 55% of the student body was male and 60% of the respondents were male. Finally, the respondents represented a wide array of majors offered at the survey university.

The students were asked a series of statements covering rationales for engaging in academic dishonesty. The statements were measured using a four-point Likert-type of response scale ranging from strongly disagree, disagree, agree, and strongly agree, and were adapted from Sutton and Huba (1995). About 49% of the students strongly disagreed that cheating was justified to receive a better grade in a course, while 38% disagreed, 10% agreed, and 3% strongly agreed. When asked if cheating was justified when a friend asked for help during an exam, 3% strongly agreed that it was, 11% agreed, 42% disagreed, and 44% strongly disagreed. Only 3% strongly agreed that cheating was justified when a person needs to keep a scholarship or financial aid, while 12% agreed with the statement, 42% disagreed, and 43% strongly disagreed. When asked if cheating was justified when a person needed to pass a course to stay in school, 5% strongly agreed, 17% agreed, 41% disagreed, and 38% strongly agreed. Only 6% strongly agreed that cheating was justified when a person needed to pass a course for graduation, 16% agreed, 41% disagreed, and 37% strongly disagreed. Additionally, respondents were asked if cheating was justified when a person needed a certain grade point average to get into a specific major. Three percent strongly agreed that it was justified, 10% agreed that it was justified, 46% disagreed that it was justified, and 41% strongly disagreed that cheating was justified in this case. As previously indicated in the literature review, these justifications have been found to be associated with cheating. Finally, students were also asked about the morality of justifying cheating (i.e., “Cheating is never justified under any circumstances”).

Since past research has shown discussing the subject decreases cheating, the respondents were asked if they had ever taken a course on ethics. Seventy-six percent marked that they had not taken a course on ethics, and 24% indicated that they had a course on ethics. Two questions on religion were selected for this study as well. Specifically, the students were asked “To what extent has religion played a major role in your life?” About 21% indicated a great deal, 40% a fair amount, 26% not much, and 13% not at all. The students were also asked if religion had played a part on their views toward academic dishonesty. Approximately 18% indicated a great deal, 30% a fair amount, 25% not much, and 28% not at all. The religious questions were adapted from Sutton and Huba (1995).

A measure of deterrence is also included in this study. Respondents were asked how fearful they were of being caught cheating. About 15% indicated they were not fearful at all, 57% somewhat fearful, 20% fearful, and 9% very fearful. Additionally, a measure of frequency of past academic dishonesty in high school was included on the survey, since research has shown one of the best predictors of future behavior is past behavior. Almost 14% of the students indicated that they had never engaged in academic dishonesty while in high school, slightly over 34% marked that they rarely cheated in high school, 33% occasionally did so, 13% did so often, and 6% did so very often.

The dependent variable in this study is academic dishonesty. Since there are many different forms of academic dishonesty, rather than limit the study to only a handful of dishonest behaviors, we decided to ask about numerous different types of cheating. The questions on academic dishonesty were adopted from questions from Stern and Havlicek (1986) and Eskridge and Ames (1993). In these studies over thirty questions on academic dishonesty were asked. Due to time constraints in administering the survey, we limited the number of questions to twenty. The specific forms of academic cheating asked are listed in the appendix. The questions covered a wide array of collegiate cheating behaviors. The response categories were based on the number of times a person committed the particular cheating behavior. Specifically the response categories were 0, 1, 2, 3 to 5, and 6 and more times.

Based upon the frequency of self-reported cheating behaviors listed in the appendix from most frequently reported to the least frequently reported (percentages available upon request), two conclusions can be drawn. First, only a minority of students admit to engaging in any particular form of cheating except “Working in a group on a homework assignment that was assigned as individual work,” which 50% of students admitted. That is, on all but 1 of the 20 forms of academic dishonesty asked about, more than 50% of the respondents indicated that they had never engaged in that particular cheating behavior while in college. Additionally, as a general trend, the less serious forms of academic dishonesty are more common than the more serious forms. This is not surprising, since similar findings have been observed with other negative behaviors, such as crime. The second conclusion that can be drawn is that very few students report that they engage in particular cheating behaviors frequently. Specifically, very few of the students indicated that they have engaged in a particular form of cheating three or more times.

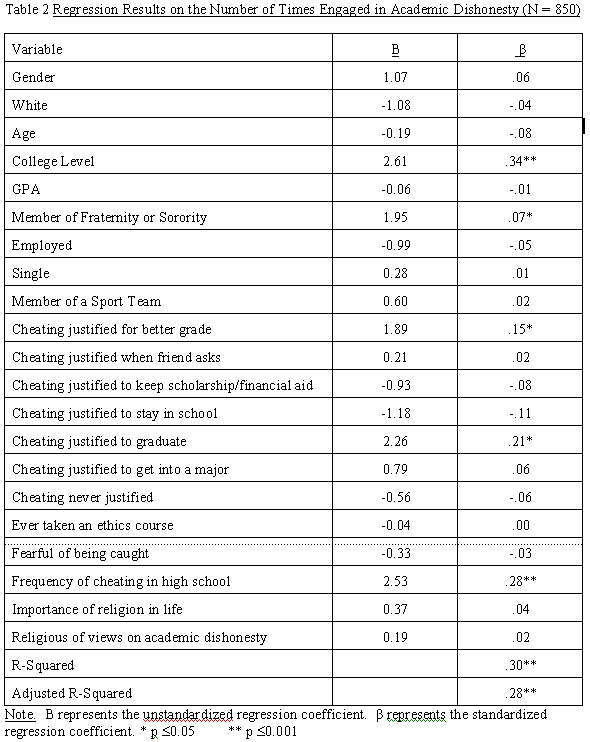

Next, multi-variate analysis was conducted to see which of the correlates measured would be significant predictors of cheating. The dependent variable was total cheating behavior, a variable computed by summing the responses to the twenty forms of academic dishonesty. A score of zero indicated that a student has never engaged in any of the forms of academic dishonesty measured. The greater the score, the more times a student had admitted to cheating. The summed measure ranged from 0 to a maximum value of 80. The mean was 8.18, with a standard deviation of 9.39. Only 17% of the students indicated that they had never engaged in any of the forms of cheating measured. Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression was computed with the summed academic dishonesty measure as the dependent variable, and the nine demographic characteristics (i.e., gender, race, age, college level, GPA, member of fraternity/sorority, employed, single or not, and a member of sports team), the seven justifications for cheating, if they had ever taken an ethics course, fear of being caught, frequency of cheating in high school, and the two religious questions as the independent variables. The results are reported in Table 2.

The adjusted R-squared was .28. Thus, the 21 independent variables in the OLS regression equation accounted for 28% of the variation observed in the dependant variable of academic dishonesty. Of the 21 independent variables, only five had significant effects on the summed academic dishonesty measure. Of the nine demographic measures, only college level and fraternity/sorority membership had statistically significant effects. As college level increase, the level of academic dishonesty also increased. Those students who belonged to a fraternity or sorority were more likely to have high rates of academic dishonesty than were students who did not belong to a social Greek organization.

The two justification measures were significantly related to the total level of cheating reported by the students. Specifically, cheating was justified for a better grade and cheating was justified to graduate were significant. As agreement with either justification increased, so to did the level of cheating. The other five justification measures had only insignificant effects.

Frequency of cheating in high school had a significant effect. The more frequently a student reported cheating in high school, the higher the level of reported cheating in college. On the other hand, there was no difference in the level of academic dishonesty between students who had taken a previous ethics course and those students had not. Similarly, the degree of fear of being caught had no significant association with the total level of cheating. Finally, neither the degree of importance of religion in a person’s life nor religious views on cheating had a statistically significant impact on the academic dishonesty variable.

Looking at the magnitude of effects (i.e., the standardized coefficient, β in Table 2), college level had the greatest impact, followed closely by the measure of frequency of high school cheating. The justification of cheating to graduate was next and had a larger effect than did the justification of cheating for a better grade. Finally, the variable measuring membership in a fraternity or sorority had the smallest effect among the five statistically significant independent variables.

There are two interesting findings that need to be addressed. First, the prevalence of academic dishonesty on a college campus is significantly influenced by how it is measured. Second, many of the bivariate associations reported in the literature (and replicated here but not reported) were not found in the multi-variate analysis.

As indicated, the findings suggest that the method of measuring academic dishonesty influences the results. When the individual forms of cheating in the appendix are measured, the majority (i.e., 50% or more) of students indicated that they have not engaged in that particular form of academic dishonesty. Thus, if a limited range of behaviors were measured and reported as individual measures, it could be concluded that academic dishonesty is not a common problem. On the other hand, when using the summed measure of academic dishonesty, the vast majority (83%) of students indicated that they have cheated, and done so more than once. Therefore, when a summed measure based upon a wide range of cheating behaviors is used, it would be concluded that cheating on this campus is both frequent and prevalent, as has been found in other studies. Academic dishonesty encompasses a wide range of behaviors that clearly cannot be assessed with a single measure. Even in this study, only a limited range of cheating was measured. Future research needs examine how different measurements of academic dishonesty influence the results.

Most of the bivariate relationships reported in the literature were not observed in the OLS analysis. This suggests that once other measures are controlled for, many correlates have little overall effect on the total level of academic dishonesty. While many past studies have focused on personal characteristics, such as age, gender, marital status, GPA, and so forth, the findings in this study suggest that most personal characteristics are not salient predictors of cheating. The nine personal characteristics used in this study only accounted for 10% of the variance of the summed academic dishonesty measure. It should also be noted that the other variables explain a greater amount of the variance of the summed academic dishonesty variable than do the personal characteristics measures. Moreover, in multi-variate analysis, only two of the nine personal variables had significant relationship (i.e., college level and fraternity/sorority membership). This implies that relationships between personal characteristics and academic dishonesty in other studies may have been observed because personal characteristics are proxy measures for other reasons for cheating. Future research in academic dishonesty needs to move beyond simply looking at differences in the levels of cheating based upon personal characteristics and focus more the underlying causes.

As with demographic characteristics, the seven justification frequently presented in the literature that are correlated with academic dishonesty were not found in the multi-variate analysis. Of the seven justification measures, only two had a significant effect on the cheating measure. Specifically, justification for a better grade and justification to graduate both had significant positive effects. After controlling for the effects of other independent variables, the other five justifications found in the literature appear to have no significant effects on the dependent cheating variable. The two significant justification measures represent the greatest outcomes possible for cheating, a better grade and graduation. Thus, as the potential rewards for cheating increase, it appears that so to does the frequency of academic dishonesty, at least in this study. In addition, most students in this study are not very fearful of being caught cheating. This lack of fear may be appropriate, since the literature suggests the chances of being caught are relatively low (Diekhoff et al., 1996, 1999; Falleur, 1990; LaBeff et al., 1990; Tibbetts, 1998) and the punishments are frequently mild and many times not supported by the university administration (Bailey, 2001).

For many behaviors, past behaviors are often the best predictors of current behaviors. It appears that students who cheated in high school continue to do so in college. The two religious measures had little effect on academic dishonesty. It could be that for most college students cheating and religion are separate focuses, even when they may be in conflict with one another. A course on ethics had no impact on frequency of cheating. Students may not apply what they learned in the ethics course to other courses where they may cheat. In addition, it is unclear to what degree academic dishonesty is stressed in an ethics course. Future research needs to examine why religion and exposure to religion have little, if not impact, on overall level of academic dishonesty. In addition, future research should determine whether these findings can be replicated or were due to random chance.

Moreover, only a small amount of the level of cheating was accounted for by the measures in this study. Specifically, the 21 independent variables explained 28% of the variance observed in the dependent variable. This means that 72% of the variance in frequency in cheating was accounted for other factors. It should be noted that in other studies very little of the cheating could be explained by the independent variables (e.g., less than 20% of the variance in the dependent academic dishonesty measure was accounted for in studies by Cochran et al. (1998) and Cochran et al. (1999), 16% in a study by Jordan (2001), 30% in a study by McCabe & Trevino (1997), and 4% in a study by Pulvers & Diekhoff (1999)). Since much of variance of frequency of cheating observed among students has not been accounted for in this and other studies, clearly additional research is needed.

There are many other areas that should be measured and included in future multi-variate analyses on academic dishonesty. Personality may be a factor in explaining the differences observed in types and frequency of academic dishonesty (DePalma, Madey, & Bornschein, 1995; Perry, Kane, Bernesser, & Spicker, 1990). Future research may wish to incorporate measures of rational choice theory (Tibbetts, 1999), social learning theory, (Michaels & Miethe, 1989), and social control (Micheals & Miethe, 1989). Future studies should include measures for social pressures to cheat or not to cheat. Future studies should include in the multi-variate analysis measures for studying habits, since there is a suggestion that those with poor study habits may be more likely to cheat (Houston, 1986; Kerkvliet, 1994). Besides sports, Greek membership, and varsity sports, other types of types of “extracurricular” activities, such as partying and drug use should be studied (Whitley, 1998). Moreover, future research should test theoretical explanations of why some and not other students cheat. The current study was atheoretical in that it only tested the significance of correlates reported in the literature in a multi-variate analysis. In addition, this study proposes no specific methods to curb collegiate academic dishonesty.

There is a growing body of literature suggesting particular methods to combat academic dishonesty (e.g., Brown & Howell, 2001; Genereux & McLeod, 1995; Kibler, 1993; May & Loyd, 1993; McCabe & Trevino, 1993; McCabe, Trevino, & Butterfield, 2001). While means to combat academic dishonesty are clearly needed, more research on collegiate academic dishonesty is needed. The findings of this study suggest that there is much more research needed to fully understand what types of cheating students engage in, how frequently they cheat, and why they cheat. Knowing what areas students cheat, how frequently they cheat, and, most importantly, why they cheat is of both theoretical and practical importance.

Despite a continued concern for ethical behavior and integrity, dishonesty still remains an endemic problem in the collegiate setting. Academic institutions and programs have added ethics courses in attempts to create a value-driven education. Yet students cheat in a variety of ways for a variety of reasons. As seen in this study, justifications for cheating are specifically given to pass a course or to graduate. This then calls into question the actual knowledge that students are learning in the undergraduate setting. Since previous studies have indicated that academic dishonesty occurs across majors, students who will eventually be entrusted with life sustaining decisions (i.e., physicians, police officers) may not be as prepared as society expects.

This study was limited to one Midwestern university. Additional research using multi-variate analysis at different academic institutions can determine whether these results were unique or can be generalized to college students in general.

In conclusion, future research should look at the academic system to see whether it discourages or contributes to student academic dishonesty. Examining faculty perceptions of cheating behaviors as well as collegiate response to allegations of cheating may uncover an understanding of why students are not fearful of repercussions in response to their actions. It is time to create a course of action that discourages dishonesty. However, this can only be done once the problem is better understood, including the salient correlates and causes of academic dishonesty.

The authors thank Janet Lambert for proofreading and editing the paper. The authors also thank the reviewers for their comments and suggestions.

Forms of Academic Dishonesty Measured. The response options were 0, 1, 2, 3 to 5, and 6 and more times.

Aiken, L. R. (1991). Detecting, understanding, and controlling for cheating on tests. Research in Higher Education, 32, 725-736.

Antion, D. L. & Michael, W. B. (1983). Short-term predictive validity of demographic, affective, personal, and cognitive variables in relation to 2 criterion measures of cheating behaviors. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 43, 467-483.

Arent, R. (1991). To tell the truth. Learning, 19 (6), 72-73.

Bailey, P. A. (2001). Academic misconduct: Responses from Deans and Nurse Educators. Journal of Nursing Education, 40 (3), 124-131.

Baird, J. S. (1980). Current trends in college cheating. Psychology in Schools, 17, 515-622.

Blankenship, K. L. & Whitley, B. E. (2000). Relation of general deviance to academic dishonesty. Ethics & Behavior, 10, 1-12.

Brown, V. J., & Howell, M. E. (2001). The efficacy of policy statements on plagiarism: Do they change students’ views? Research in Higher Education, 42, 103-118.

Brownell, H. C. (1928). Mental traits of college cribbers. School and Society, 27, 764.

Bunn, D., Caudill, S., & Gropper, D. (1992). Crime in the classroom: An economic analysis of undergraduate student cheating behavior. Research in Economic Education, 23, 197-207.

Caruana, A., Ramaseshan, B., & Ewing, M. T. (2000). The effect of anomie on academic dishonesty among university students. The International Journal of Educational Management, 14, 23-30.

Chop, R., & Silva, M. (1991). Scientific fraud: Definitions, policies, and implications for nursing research. Journal of Professional Nursing, 7 (3), 166-171.

Cochran, J. K., Chamlin, M. B., Wood, P. B., & Sellers, C. S. (1999). Shame, embarrassment, and formal sanction threats: Extending the Deterrence/Rational Choice Model to academic dishonesty. Sociological Inquiry, 69, 91-105.

Cochran, J. K., Wood, P. B., Sellers, C. S., Wilkerson, W., & Chamlin, M. B. (1998). Academic dishonesty and low self-control: An empirical test of a General Theory of Crime. Deviant Behavior: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 19, 227-255.

Coleman, N., & Mahaffey, T. (2000). Business student ethics: Selected predictors of attitudes toward cheating. Teaching Business Ethics, 4, 121-136.

Coston, C. T. M., & Jenks, D. A. (1998). Exploring academic dishonesty among undergraduate criminal justice majors: A research note. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 22, 235-248.

Davis, S. (1992). Academic dishonesty: Prevalence, determinants, techniques, and punishments. Teaching of Psychology, 19, 16-20.

Davis, S. F., Grover, C. A., Becker, A. H., & McGregor, L. N. (1992). Academic dishonesty: Prevalence, determinants, techniques, and punishments. Teaching Psychology, 19, 16-20.

DePalma, M. T., Madey, S. F., & Bornschein, S. (1995) Individual differences and cheating behavior: Guilt and cheating in competitive situations. Personality and Individual Differences, 18, 761-769.

Diekhoff, G. M., LaBeff, E. E., Clark, R. E., Williams, L. E., Francis, B., & Haines, V. J. (1996). College cheating: Ten years later. Research in Higher Education, 37, 487-502.

Diekhoff, G. M., LaBeff, E. E., Shinohara, K., & Yasukawa, H. (1999). College cheating in Japan and the United States. Research in Higher Education, 40, 343-353.

Eskridge, C., & Ames, G. A. (1993). Attitudes about cheating and self-reported cheating behaviors of criminal justice majors and noncriminal justice majors: A research note. Journal of Criminal Justice Education, 4, 65-78.

Eve, R., & Bromley, D. G. (1981). Scholastic dishonesty among college undergraduates: Parallel test of two sociological explanations. Youth and Society, 13, 3-22.

Falleur, D. (1990). An Investigation of academic dishonesty in allied health: Incidence and definitions. Journal of Allied Health, Fall, 314-323.

Fass, R. (1986). By honor bound: Encouraging academic honesty. Educational Record, 67 (4), 32-36.

Gardner, W. M., Roper, J. T., Gonzalez, C. C., & Simpson, R. G. (1988). Analysis of cheating on academic assignments. The Psychological Record, 38, 543-555.

Genereux, R. L., & McLeod, B. A. (1995). Circumstances surrounding cheating: A questionnaire study of college students. Research in Higher Education, 36, 687-704.

Hagan, F. (1997). Research methods in criminal justice and criminology (4th ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Haines, V. J., Kiefhoff, G. M., LaBeff, E. E., & Clark, R. (1986). College cheating: Immaturity, lack of commitment, and neutralizing attitude. Research in Higher Education, 25, 342-354.

Hilbert, G. A. (1985). Involvement of nursing students in unethical classroom and clinical behaviors. Journal of Professional Nursing, 1, 230-234.

Hollinger, R., & Lanza-Kaduce, L. (1996). Academic dishonesty and the perceived effectiveness of counter measures: An Empirical survey of cheating at a major public university. NASPA Journal, 34, 292-306.

Houston, J. P. (1983). Kohlberg-type moral instruction and cheating behavior. College Student Journal, 17, 196-204.

Houston, J. P. (1986). Survey corroboration of experimental findings on classroom cheating behavior. College Student Journal, 20, 168-173.

Jendrek, M. P. (1992). Student reactions to academic dishonesty. Journal of College Student Development, 30, 401-406.

Jordan, A. E. (2001). College student cheating: The role of motivation, perceived norms, attitudes, and knowledge of institutional policy. Ethics & Behavior, 11, 233-247.

Kibler, W. L. (1993). Academic dishonesty: A student development dilemma. NASPA Journal, 30, 252-267.

Kirkvliet, J. (1994). Cheating by economic students: A comparison of survey results. Journal of Economic Education, 25, 121-133.

LaBeff, E. E., Clark, R. E., Haines, V. J., & Diekhoff, G. M. (1990). Situational Ethics and College Student Cheating. Sociological Inquiry, 60, 190-198.

Lanza-Kaduce, L., & Klug, M. (1986). Learning to cheat: The interaction of moral development and social learning theories. Deviant Behavior, 7, 243-259.

Leming, J. S. (1980). Cheating behavior, subject variables, and components of the internal-external scale under high and low risk conditions. Journal of Educational Research, 74, 83-87.

May, K. M., & Loyd, B. (1993). Academic dishonesty: The honor system and students’ attitudes. Journal of College Student Development, 34, 125-129.

McCabe, D. L. (1992). The influence of situational ethics on cheating among college students. Sociological Inquiry, 62, 365-374.

McCabe, D. L., & Bowers, W. J. (1994). Academic dishonesty among college males in college: A thirty year perspective. Journal of College Student Development, 35, 5-10.

McCabe, D. L., & Trevino, L. K. (1993). Academic dishonesty: Honor codes and other contextual influences. Journal of Higher Education, 64, 520-538.

McCabe, D., & Trevino, L. (1996). What we know about cheating in college. Change, January/February, 29-33.

McCabe, D. L., & Trevino, L. K. (1997). Individual and contextual influences on academic dishonesty: A multicampus investigation. Research in Higher Education, 38, 379-396.

McCabe, D. L., Trevino, L. K., & Butterfield, K. D. (2001). Dishonesty in academic environments. The Journal of Higher Education, 72, 29-45.

McNichols, C. W., & Zimmerer, T. W. (1985). Situational Ethics: An Empirical Study of Differentiators of student attitudes. Journal of Business Ethics, 4, 175-180.

Meade, J. (1992). Cheating: Is academic dishonesty par for the course? Prism, 1 (7), 30-32.

Michaels, J. W., & Miethe, T. D. (1989). Applying theories of deviance to academic cheating. Social Science Quarterly, 70, 872-885.

Mixon, F. (1996). Crime in the classroom: An extension. Journal of Economic Education, 27, pp.195-200.

Moore, T. (1988). Colleges try new ways to thwart companies that sell term papers. Chronicle of Higher Education, 25 (11), A1, 36.

Newhouse, R. C. (1982). Alienation and cheating behavior in the school environment. Psychology in Schools, 10, 234-237.

Newstead, S. E., Franklyn-Stokes, A., & Armstead, P. (1996). Individual differences in student cheating. Journal of Educational Psychology, 88, 229-241.

Packer, S. (1990). Students’ ethics require new ways to cope with cheating. Journalism Educator, 44 (4), 57-59.

Pavela, G. (1978). Judicial review of academic decision-making after Horowitz. School Law Journal, 55, 55-75.

Pavela, G. (1997). Applying the power of association on campus: A model code of academic integrity. Journal of College and University Law, 24, 97-118.

Perry, A. R., Kane, K. M., Bernesser, K. J., & Spicker, P. T. (1990). Type A Behavior, Competitive Achievement-Striving, and Cheating Among College Students. Psychological Reports, 66, 459-465.

Pratt, C., & McLaughlin, G. (1989). An analysis of predictors of students’ ethical inclinations. Research in Higher Education, 30, 195-219.

Pulvers, K., & Diekhoff, G. M. (1999). The relationship between academic dishonesty and college classroom environment. Research in Higher Education, 40, 487-498.

Robinson, V. M. J., & Kuin, L. M. (1999). The explanation of practice: Why Chinese students copy assignments. Qualitative Studies in Education, 12, 193-210.

Roig, M., & Ballew, C. (1994). Attitudes toward cheating of self and others by college students and professors. The Psychological Record, 44, 3-12.

Roig, M., & DeTommaso, L. (1995). Are college cheating and plagiarism related to academic procrastination? Psychological Reports, 77, 691-698.

Scheers, N. J., & Dayton, C. M. (1987). Improved estimation of academic cheating behavior using the randomized response technique. Research in Higher Education, 26, 61-69.

Simpson, D. (1989). Medical students’ perceptions of cheating. Academic Medicine, 64, 221-222.

Singhal, A. C. (1982). Factors in student’s dishonesty. Psychological Reports, 51, 775-780.

Smith, R. E., Wheeler, G., & Diener, E. (1975). Faith without works: Jesus people, resistance to temptation, and altruism. Journal of Applied Psychology, 5, 320-330.

Spiller, S., & Crown, D. (1995). Changes over time in academic dishonesty at the collegiate level. Psychological Reports, 76, 763-768.

Stern, E. B., & Havlicek, L. (1986). Academic misconduct: Results of faculty and undergraduate student surveys. Journal of Allied Health, 5, 129-142.

Stevens, G. E., & Stevens, F. W. (1987). Ethical inclinations of tomorrow’s managers revisited: How and why students cheat. Journal of Education for Business, October, 24-29.

Sutton, E. M., & Huba, M. E. (1995). Undergraduate student perceptions of academic dishonesty as a function of ethnicity and religious participation. NASPA Journal, 33, 19-34.

Sykes, G., & Matza, D. (1959). Techniques of neutralization: A theory of delinquency. American Sociological Association, 22, 664-670.

Tang, S., & Zuo, J. (1997). Profile of college examination cheaters. College Student Journal, 31, 340-346.

Tibbetts, S. G. (1998). Differences between criminal justice majors and noncriminal justice majors in determinants of test cheating intentions. Journal of Criminal Justice Education, 9, 81-94.

Tibbetts, S. G. (1999). Differences between women and men regarding decisions to commit test cheating. Research in Higher Education, 40, 323-342.

Tibbetts, S. G., & Myers, D. L. (1999). Low self-control, rational choice, and student test cheating. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 23, 179-200.

Tom, G., & Borin, N. (1988). Cheating in academe. Journal of Education for Business, 63, 153-157.

Von Dran, G. M., Callahan, E. S., & Taylor, H. V. (2001). Can students’ academic integrity be improved? Attitudes and behaviors before and after implementation of an academic integrity policy. Teaching Business Ethics, 5, 35-58.

Ward, D. A. (1986). Self-esteem and dishonest behavior revisited. Journal of Social Psychology, 123, 709-713.

Ward, D. A., & Beck, W. L. (1990). Gender and dishonesty. The Journal of Social Psychology, 130, 333-339.

Weaver, K. A., Davis, S. F., Look, C., Buzzanga, V. L., & Neal, L. (1991). Examining academic dishonesty policies. College Student Journal, 23, 302-305.

Weiss, J., Gilbert, K., Giordano, P., & Davis, S. F. (1993). Academic dishonesty, Type A behavior, and classroom orientation. Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society, 31, 101-102.

Whitley, B. E. (1998). Factors associated with cheating among college students: A review. Research in Higher Education, 39, 235-274.

© Electronic Journal of Sociology