Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

G. Coates

Contemporary performance appraisal (PA) has become an important tool in the overseeing of employees in work. Little of the vast literature however, has focused on its effects on the individual, beyond simple descriptions that inform its management implementation. This article firstly examines the changing nature of employee management under PA, before it investigates the contemporary usage of PA and the effects on women. This is illustrated with research, gathered from a case study in the Midlands. The article also examines the changing focus of PA as a means through which the marginal, and not so marginal performer can be controlled. Analysis focuses on the use of subjective images of ‘women’, through PA, for creating functionally flexible workers in a ‘quality’ environment. This analysis also examines management’s attempts to ‘involve’ individuals in the formulation of their own work process. It does this by focusing on the powerful subjective manipulation of knowledge over individuals. The use of a hospital case study highlights some of these issues in relation to the changes taking place in the public service sector. This sector faces fundamental transformations in its concept of ‘service’.

Performance appraisal belongs to the post-modern organisational notion of a ‘human centred’, subjective management system, manifest in Human Resource Management (HRM), Strategic Manpower Planning and Total Quality Management (cf. Harrison and Laplante 1993). For many individuals, PA conjures images of piecework and performance-related-pay (PRP), and has been seen as a less than objective principle (McArdle et al. 1992). This fear has become a rational one in recent times for education (Harley and Lee 1995; Miller 1991), articulating notions of surveillance and control (Reed and Whitaker 1992).

Broadly speaking, there are two camps, those who support performance appraisal (Cotton 1993; Molander and Winterton 1994; Murphy and Cleveland 1995) and those who see it as a form of control (Causer and Jones 1996; Coates 1994).

Performance appraisal has its roots in a ‘classical theory of organisations’ with strong notions of power and control through management (Reed 1992). This management control was an attempt to overcome the problems stemming from the lack of control over manual employees. Moreover, the increasing use of performance appraisal and PRP at all levels, illustrates that the problem of intransigent employees is seen by organisations to have transferred itself to the non-manual sector (Ball 1990; Causer and Jones 1996). At this white-collar level, the planning and organising of work has been removed to the higher reaches of management, as has job autonomy, similar to shop floor employees (Cutler 1992).1

Like many other people management concepts such as organisational commitment, performance appraisal is subordinated under a notion of the ‘individual as resource’, to be drawn on and used to the full, much like machinery (Ramsey 1991; Coates 1992). In this, performance appraisal stresses both employer and employee should focus on the complementary purpose of the organisation’s furtherance. On the one hand individuals are a potential business resource through the enhancement of their personal skills. While on the other, they are seen as any other investment in equipment (cf. Cutler 1992).

Performance appraisal’s definition however, prescribes a ‘required’ outcome of productive increases in performance. Individuals, as people, are only peripherally related to it (Bartol and Martin 1991). Performance appraisal is thus a formal organisational mechanism for controlling the performance of work tasks on a rational, subjective and continuous basis, and is according to Bevan and Thompson (1991):

In essence, performance appraisal is an attempt to involve individuals in the regular clarification of their work tasks, goals and achievements, at the same time making them more accountable for them (James 1988).

Such management practices accentuate one aspect in particular for performance appraisal. With the move away from a direct and technical supervision of work towards a discretionary or self-management aspect, performance appraisal has become the means to monitor the form in which this discretion is understood and practised. This discretionary feature has come about partly through technological changes in the work process, and partly a desire to achieve flexibility through the elimination of job descriptions and union staffing requirements. It has also been the attempt to adopt ‘Japanese’ employment practices (Abe and Gourvish 1997; Cutcher-Gershenfeld et al 1998). Here adoption of ‘shared meanings’ and ‘strong culture’ – the internalisation of corporate morals, values and attitudes – becomes primary. Performance appraisal serves as a mechanism to measure such internalisation. Explicit rules play a lesser role in the regulation of performance.

Recent debate goes deeper than humble performance, moving towards the use of performance appraisal as a way for employees to identify with their organisation (e.g. Coates 1994). Hence the debate which argues performance appraisal is a means to involve individuals in their own subordination (e.g. Sturdy et al 1992). Townley (1994), using Foucault, has called this the acquisition of ‘implicit expectation’ in the performance of work; i.e. employees become drawn into ‘the subjective realm’ of their managers’ aspirations for output and performance. This for Foucault (1974) was the development of a technology of power and domination. Knowledge, he argued, always supports several truth claims that are an intrinsic part of the struggle for power within human groups. Here truth is imposed on the world by the powerful. Knowledge is therefore always the intimate of power. As performance appraisal is a form of knowledge over individuals through appraisal files, it is also power over them. Central to Foucault’s argument, is the belief that knowledge reflects power and authority positions. It therefore embodies both meaning and social relationships. They:

… are not about objects; they do not identify objects, they constitute them and in the practice of doing so conceal their own invention. (Foucault 1974:49)

For managers performance appraisal is seen to provide the information to direct and control employees in white-collar work where there are fewer physical performance outcomes. Moreover, over thirty years ago McGregor (1960:75) argued that:

Appraisal programs [we]re designed … to provide more systematic control of the behaviour of subordinates.

This article, through case study analysis, examines the changing focus of performance appraisal as a means through which the marginal, and not so marginal performer can be controlled. Analysis focuses on the level of the experience of subjective images of ‘women’, through performance appraisal, for creating functionally flexible workers in a ‘quality’ environment (Hill 1991). This analysis also examines management’s attempts to ‘involve’ individuals, at a deep level, in the formulation of their own work process. It does this by focusing on the powerful subjective manipulation of knowledge over individuals. Space does not allow the analysis to engage with the vast literature on performance appraisal, the article focuses on the experiences of individuals who receive its demands.

The data reported here were collected from the white-collar staff of a case study organisation, carried out between January 1994 – April 1995. The data reports interviews with the white-collar members of a large Midlands trust hospital – CareCo.2 The case study provides data on a newly formed trust management structure for an ex-NHS hospital. This hospital had introduced performance appraisal with an overture to market principles for costing treatments and GP fundholders. CareCo was chosen as it was both a first wave trust and was at the forefront of the adoption, by ex-NHS hospitals, of performance appraisal for part of its pay policy.

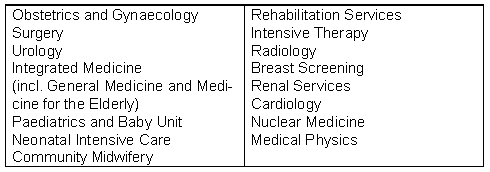

As a hospital, CareCo employs over 2,300 staff on a single site on the outskirts of a city, and is one of two major hospitals in the area. CareCo supplies specialised care for a number of areas (see appendix 1). It is also a leader in the field of breast cancer and gynaecology research/treatment. These services are not duplicated at the other trust hospital.

In all, some 200 white-collar employees were studied. Significantly this group contained both business managers and ward managers. In terms of gender, the vast majority of interviewees were women, which was true for CareCo in general (80%). However, this did not reflect their power position within the hospital, where less than 1% of the studied population were in upper management (cf. Pulkingham 1992). While there were 1840 women employed at CareCo, 40% of these were part-time in some form, as opposed to 3% of men. All whitecollar departments studied had male directors; midwifery and maternity had the largest proportion of female ward managers.

The interviews were designed to seek information concerning the nature of performance appraisal at CareCo and women’s role within it. It was also designed to ascertain the individuals’ personal experience of performance appraisal and the experience of the internalisation of CareCo’s PA policy. Interviews were semi-structured and lasted approximately an hour. These interviews were all tape recorded and later transcribed. To supplement these, a number of ‘informal’ management group meetings were also studied, as were CareCo’s newsletter meetings. These were undertaken as ‘observer-as-participant’ (Gold 1958).

Within CareCo, management were attempting to adopt market practises – PRP – for white-collar staff not directly involved in patient care, and especially those involved in senior management activities. These were part of the ‘salary progression review scheme’ that pays annual increments according to a satisfactory level of performance, determined by departmental managers and based on their individual budget surpluses.

This system had been in place for senior management since 1993 and was extended to all white-collar levels in 1994. In conjunction with this, management had particularly invested in new ways of employing individuals, including short-term contracts. Management also expressed an increasing demand for candidates who exhibited ‘charismatic’ rather than ‘bureaucratic’ personalities. Performance appraisal was undertaken annually by immediate managers and closely followed a printed form that contained a number of categories (see appendix 2). These were then commented upon by the manager in discussion with the employee. The form of performance appraisal used had been through a number of internal audits and passed satisfactorily in both 1994 and 1995. The official line was that:

The core of the [performance appraisal] process is the one-to-one dialogue, which takes place between the manager and the individual reporting directly to him or her. The effectiveness of the work process is therefore crucially dependent on the quality of the appraisal interview. (HR Director)

Performance appraisal at CareCo went beyond simple function and was designed to internalise the organisations’ aims; the position of women in this is important for understanding how women are doubly burdened with presenting ‘correct’ subjective identities (henceforth identity) that are compatible with CareCo’s aims. Women were doubly subjected, being employed and judged as employees for their looks as much as their skills (cf. Hochschild 1983):

On a number of occasions [names of two managers] have gone out of their way to employ tall blond bimbos. They aren’t suitable for the job, but they don’t care, it would damage their egos if they employed someone with intelligence. (HR Dept)

Cockburn (1985) has pointed out that employers harness and make use of women’s feelings and emotions e.g. in retail sales. Women not only sell their feminine identity, they also sell their female emotions (Truss 1993), and this is especially true for ‘caring professions’ and their ancillaries. The perception of those working in a hospital has a very strong resonance in the minds of the general population as a feminine, caring one (Strauss et al 1982). Thus women, more so than men, were subject to more than just performance appraisal images. They were also subject to societal based sexual identity management in their work lives at the hospital, where they were seen to be natural carers (cf. Chandler et al 1995). This is almost the ‘inside-out’ smile of Hochschild’s (1983) air stewardesses. Here women at CareCo had to project the applicable feminine identity traits to pass their performance appraisal. Hence an emphasis on not appearing career minded (Morgan 1990:51). This was explained at CareCo as:

Helping all staff balance work and home commitments thereby ensuring a healthy and better motivated workforce, able to deliver our business objectives continues to be a priority for us in 94/5.

However, those that presented an identity of professional manager first and femininity second, there was short shrift in store. At least two female section heads, one in the HR department and the other in the TQM department, had been placed on the ‘at risk’ register for their outspokenness. This meant their positions were no longer permanent/viable and that they would be offered suitable alternative positions – if possible. One person had found themself in this situation due to a ‘petty feud’ between herself and the male head of HR:

My job now is not funded or so the director says. I’m in a worse position now than ever as I could be out of a job come April if they say there is no money and all because of that bastard saying I wasn’t doing my job properly. Just because I spoke up when I thought a policy was wrong.

This is the development of a technology of power and domination (Foucault 1974) or knowledge over women. Foucault argued knowledge was always an intrinsic part of the struggle for power within human groups (1974). Performance appraisal is a form of knowledge over individuals through appraisal files, it is also power (control) over them as it regulates pay. Central to Foucault’s argument, is the belief that knowledge reflects power and authority positions. It therefore embodies both meaning and social relationships. They:

… are not about objects; they do not identify objects, they constitute them and in the practice of doing so conceal their own invention. (Foucault 1974:49)

Thus the knowledge on individual’s appraisal files at CareCo controlled their actions and their identification with work norms. Performance appraisal at CareCo reflected a new initiative for its control of women, and a new imperative for staff to be aware of their individual identity. Thus CareCo used performance appraisal as an exercise in selfpresentation of femininity more than a tool for delivering physical productivity improvement.

Hence a major criticism of performance appraisal at CareCo, and one that could be levelled generally, is that it actually dis-empowered women, despite its opposing rhetoric (Reed 1989). It did this firstly through filtering and monitoring values, attitudes and behaviour, reducing responsibility and increasing the homogeneous nature of the work force. For example, within CareCo’s HRM department (99% women), it was not acceptable for women to wear trousers despite it being allowed. This was due to the HR director’s preference to see women “as women” in skirts. Defiance was followed by mild disdain concerning the culprits’ legs, but issues of dress were included on the appraisal form too. Also, an image consultant was employed twice a year to ensure women were aware of what was required of them. Along with the traditional customer care doctrine, the female consultant imparted advice on styles of clothes, make-up and deportment and how to “… be a woman basically. I thought I was one?” (Respondent). These applied to all the women studied.

Secondly, performance appraisal required one individual making judgements of another, reinforcing authority relations and defining (inter)dependency, not individuality as performance appraisal prescribes. With the growth of white-collar jobs in CareCo, objective performance criteria were more difficult to establish given the nature of the work. As such, dependability, flexibility, initiative and personal contact became more critical aspects of performance. If performance appraisal were truly working for CareCo’s employees’ advantage, it would centre on empowerment, not judgement by senior managers, autonomy not productivity, thus giving women resources to conduct and ‘manage’ work. Studies in different countries have arrived at similar conclusions “women’s work is generally less autonomous, allows fewer possibilities for regulating one’s pace at work, is more restricted in space and time, and is more monotonous” (Kauppinen-Toropainen et al 1988:17). Performance appraisal has merely added to the burden at CareCo.

Many of the policies introduced at CareCo – Opportunity 2000, fostering of organisational commitment, technological changes, and training – had the potential to lead to the re-design of work and increase the role of women. However, while Opportunity 2000 was crucial to the health service at the time, CareCo issued a carefully worded policy/mission statement with four goals that ratified their commitment to it.

Goal one of the policy document sought to highlight the need to increase the participation of women in the trust at a senior level:

The trust currently has one woman in a general management position as defined in [document number]. This represents a negligible percentage of our total female workforce. However, this needs to be viewed against a background of only two vacancies at this level in the past 12 months. One of these vacancies resulted in the appointment of a woman.

CareCo’s Opportunity 2000 actions – creating a job share register, setting up of a working mothers’ group (Careers and Progression), back to work packages offering guidance and an authorised recruiter to be aware of women’s needs – while defined to ease problems, actually sustained them. Many of these had not been completed or activated and where they were, such as authorised recruiters being aware of women’s needs, those authorised were men.

Additionally, CareCo used performance appraisal to appeal to employees on the grounds of ‘moral involvement’ (Fox 1985), and the improvement of personal skills/rewards:

The trust believes that the continuance of its policies particularly in respect of career opportunities, such as development programmes, training sessions, etc., will result in the near future in a ground swell of female staff from many backgrounds, who will be well equipped to compete for and achieve appointments to senior positions. (Trust Policy Document)

The emphasis was placed upon personal achievement, which contributed to CareCo’s overall performance, not the individual’s own, which was viewed as peripheral:

As last year, providing continuing support to these [female] staff by encouraging flexible working arrangements is a priority. It makes economic and social sense in today’s market place. (Trust Policy Document)

The unofficial line at CareCo was that performance appraisal was inseparable from trust status and therefore part of the trust’s identity. CareCo believed it could not have quality and efficiency without the employment policies of similarly efficient private companies such as ICI. Performance appraisal’s meanings and definitions at CareCo were therefore pre-decided by the board, not the staff as is recommended by many textbooks (cf. Tolliday and Zeitlin 1991). This was echoed in the comments of one manager:

I know quality counts and all that, but what about my staff being worked off their feet all day, how can they be expected to smile all the time and be happy when they need to make a pharmacological decision in a tight spot – its a stressful job? If I had my way, performance wouldn’t be measured, if it takes 10 hours to sort someone’s life out, then that’s how long it takes. (Female)

The unwritten policy of CareCo’s board was that performance appraisal was a management led activity, for the benefit firstly of the organisation:

If we are to have a quality organisation providing quality care, we need a performance appraisal system which can ensure individuals meet the needs of the organisation – which are, after all, their own needs too. (Head of Finance).

Crucial for our analysis here is the understanding that the creation of identities of acceptable behaviour for performance appraisal in CareCo. belonged not to women, but to men.

Sure I feel I’ve become less of a woman since I’ve worked here, and that’s been 18 years now. At the end of the day you’ve got a job to do. If I’m not here nothing gets done.

While we do everything for our female staff, at least 160 of them will take their year’s leave of absence to have children this year alone! With that sort of turnover it’s impossible to keep fully staffed. [Why is that?] Well, we can only get 60% replacement for nursing staff and 40% replacement for non-medical staff. (Male HR Director)

Additionally CareCo’s policy documents’ third point stated that:

Over the next year we will look carefully at ensuring our trawls to fill the vacancies, pays particular reference to promoting aspects of our employment practices, which would be of particular interest to female candidates. Jobs will be designed to allow female candidates to fulfil their potential as much as is possible.

This simply reproduced the domestic division of labour (Hearn and Parkin 1987). For example, the HR director had bought a coffee percolator for himself and guests, placing this in his room. Whenever he required a cup, he would call through to his personal assistant to come in and make him one:

I don’t feel my job is to make cups of coffee. I am a trained assistant, not a skivvy!

While this can be seen simply as a sexist act, the role of ‘helping guests, being courteous and other tasks’ were written into this individual’s performance appraisal. Here such examples illustrate who had control over self-identity and the image employees were to perform to (cf. Truss 1993). Performance appraisal was a manifestation of this power over resistance, as all appraisals in the HR Department had to go through the HR Director. He expressed this intent in different terms as:

Performance appraisal requires individuals to conform to certain criteria. These can be both formal and informal.

While resistance is possible, it is tempered by the need to present the correct identity to retain employment, but also by CareCo linking white-collar employees’ work ultimately to patient care outcomes.

The policy document stated that CareCo’s performance appraisal contract was held to ennoble the individual, to respect her ‘dignity’, rights, and welfare, and through this focus, replace collective control with enlightened ‘employee relations’. The general manager espoused this dignity as:

The problem [of] trying to get across to the person that you’re not trying to give them a bad appraisal. You’re looking for the right responses all the time.

These ‘right responses’ were never articulated to this interviewer, but were known throughout CareCo’s board.

The difficulty with performance appraisal at CareCo was its judgmental processes, which evoked defence mechanisms aimed at protecting self-identity (Shamir 1990). Some individuals felt that while they had performed and were ‘CareCo people’, CareCo did not recognise their identity with its values:

I had my review the other day. They said that I wasn’t performing to my best ability and if I didn’t buck my ideas up I would be given a formal warning. I’ve done all I can to meet the objectives I’m set, they just keep moving them. I’m pissed off with being victimised by them because I can actually do my job and they don’t want to pay me PRP.

While the preceding argument concerning identity and performance appraisal might appear based on a contemporary economic imperative for CareCo, it is also crucially based in an understanding of the subjective relationship individuals have with hospitals and the work that goes on within.

The means through which women were made subjects was decision-making discretion. This arose through the chairman’s desire to achieve flexibility in staffing. For the chairman, any explicit rules played a negligible role in the regulation of performance – though they still existed. More primary was the adoption of the mission statement and its shared meanings and values – the internalisation of CareCo values, attitudes and norms. Individuals were able to enhance their promotion prospects by fitting in (Keating and Witkin 1992), by becoming CareCo centred individuals, aligning reflexively towards their tasks and the co-operative environment in which those tasks were undertaken:

There is only one way an individual is going to get anywhere here, and that’s by becoming a CareCo person. You have to be agreeing with the CareCo doctrine at all times. (Staff Development)

To ‘fit in’ at CareCo, women were pressured to express their feminine traits, not overtly, but covertly as part of the doctrine of ‘Quality Care’ specified in the CareCo mission statement (cf. Sims et al. 1993). This posed a contradiction for the women due to their domestic roles/commitments. They were expected, for example, to staff the human resources office 24 hours a day until someone pointed out that they had other domestic responsibilities. Afterwards they were still expected to set aside one late – 7pm – evening a fortnight as work time, there was no overtime or in lieu time.

Correspondingly, there was less room for an overtly instrumental – monetary – relationship between employee and CareCo. As Keating and Witkin (1992) illustrated, implementation and effectiveness of performance appraisal policies require that employees accept the new order and fit ‘its’ requirements. Control becomes embedded within employees’ commitment to the organisation and its goals. Hence managerial control at CareCo, was legitimated by market logic and its ability to compete effectively in the local care market. Within CareCo such commitment practices constituted identifying with the Trust’s notion of quality:

We at CareCo are dedicated to the provision of a quality service, at a quality price. You can’t have one without the other, not in my book. I want this hospital to be known for its quality. Staff must identify with this ethos. (General Manager)

Appraisal was thus extremely problematic in CareCo as its emphasis sought to create a flexible employee with attachment to the hospital, not jobs or departments, and not necessarily each other. It was crucially promoted through the use of performance appraisal, but also a trust magazine edited by a man (all reporters were women), who ‘rewrote’ all copy to express what he thought was the trust view on each issue. Additionally, rituals such as meetings and work-time social gatherings were also used to evoke, or were meant to, feelings of trust community and pride (cf. Rohlen 1980).

Performance appraisal was thus viewed by the board as the need to achieve control while disguising it, to tap employee compliance and effort through delegation, ensuring its responsible use. However, within this there was little space at CareCo for women or their expression of identities not immediately recognisable as feminine.

To present the correct identity, for example, of a ‘CareCo manager’, a woman must present the subjectified image of womanhood by which she was first judged. Then, and only then, does the ability to perform the task come into the reckoning. In spite of attempts to promote the identity of good employee, it is the feminine qualities CareCo judged women on. It was the way to identity/recognition and so to the required PA outcome:

I wouldn’t mind wearing trousers to the office once and a while, it’s a lot easier and warmer – our office is so cold. But it’s not allowed, well, officially it is, but [the HR Director] doesn’t like women in trousers, he’s a bit of a sexist really, but he does have a point. (HR Dept)

In certain cases, emphasis on femininity has lead to sexual abuse3 at CareCo and to individuals feeling their self-identity had been seriously invaded (cf. Kramer 1989). Any legal regulation and redress still proves inept and outmoded (York 1989).

This integration of CareCo’s identity into their own caused women to see themselves in light of their appraisal. Hence performance appraisal at CareCo to return to Foucault’s terms, was a ‘moral technology’ – a technology of power. It is the modern equivalent of Bentham’s panopticon “a generalizable model of functioning; a way of defining power relations in terms of the everyday life of men [sic]” (Foucault 1979:205). The management of identity at CareCo became an exercise in control over women. Unlike the panopticon, it was not about being able to observe at all times the individual’s body, but internalising control until individuals were watching over their own bodies/identities (Sewell and Wilkinson 1993). Therein lies the emphasis on performance appraisal outcomes, because once an individual structures their activity according to their review, they come to hold it to be a representation of themselves and seek, subjectively, to conform to it. Thus as Littler and Salaman (1982:259) argue:

once this conception of management has been accepted by workers, they have in effect, abdicated from any question of or resistance to, many aspects of their domination.

Within CareCo performance appraisal was a form of power (collecting performance information) laying claim to certain knowledge about individuals. This cast employees as subjects of that power and hence the recipients of the procedures enacted on the basis of it – such as disciplinary hearings. Consequently within CareCo women became over exposed to power and control, and thus subject to knowledge concerning their femininity through performance appraisal. Excessive time off with sick children led to performance targets being missed this being noted in appraisals.

Performance appraisal also produced the things about which it spoke – a need for appraisal. The results of appraisals proved to management that female employees were seen to be not meeting the individual criteria laid down, which led, for example, to the need for image consultants. Hence appraisal supported the need for its own creation. In doing this performance appraisal made women employees known – in the process disregarding their fears – through the use of personal information collected as part of the appraisal process. Thus the individual employees became their appraisal outcome.

CareCo’s use of personnel files permitted women to be fixed in a web of objective codification (Rabinow 1986), allowing the line manager to become a key tool of the ‘moral technology’ of management. Appraisal made women calculable, describable and comparable (through the disciplining practices of paid external image consultants, castigation and expectation), opening them to an evaluating eye and to its disciplinary power. Foucault (1979:175) described this as examination that “combines the techniques of an observing hierarchy and those of a normalizing judgement. … It establishes over individuals a visibility through which one differentiates and judges them”.

Performance appraisal could be seen as insidious at CareCo as it had no feelings, respected nothing and no one. It introduced individuality in order to punish and produced written records of effort/ability in order to punish (cf. Foucault 1979:175). At CareCo the appraisal interview was used as a formal ritual of power and ceremony of visibility (appointments were made and treated as job interviews) – a technology of objectification. It linked the formation of knowledge with the display of power. Consider here the use of notions of femininity by the human resources director to constrain identity presentation and the subjugation of self. Those appraised were there to be known and recorded by the appraiser. Hence they became ‘known’ individually through their performance appraisal outcomes. Appraisal techniques have been developed and legitimated at CareCo, insofar as they coopt women and established notions of professionalism into their subjugation. At CareCo this professionalism might well be the notion of quality care:

Quality [is] course quality is a priority, I don’t care what anyone else has said, a quality service is the goal of this hospital. Without it we fail to provide even the most basic decencies at a time of human frailty. I expect the highest quality service from my women, all staff in fact. Performance appraisal and performance related pay are just the mechanisms through which we reward people for a quality job well done. (General Manager)

All of this can be seen in the way performance appraisal at CareCo acted like the church confessional. Critically, the performance appraisal outcome at CareCo had elements of Foucault’s confessional encounter. The authority of the confessor – heads of department at CareCo – comes from the potency of the trust’s credo or mission statement to provide quality care and meet in/out -patients service standards. The premise of course is that the individual is in need of confession, that there has been transgression. Appraisal provides the information whereby employees are encouraged to display their shortcomings, to seek out or identify appropriate therapeutic (remedial) procedures and to award their own punishment (of more targets/increased output). Confession of personal failure at CareCo became part of the greater (Trust) faith; employees could not become “quality people” until they had humbled themselves before the “quality facilitator” (appraiser) and resolved to repent. The problem here was that there had to be something to confess. Individuals found themselves searching desperately for their own failures; to have none was worse than having lots. The design of the appraisal form was crucial here to a perception of the confession:

The appraisal form has all these sections on it about what you’ve done wrong in the time since your last. Writing nothing is as bad as writing the truth I think, you cant win in the end, I’ve tried and all I get is [the appraiser] writing in what he thought my faults were. I wanted to tell him that I was pissed off with Caroline’s attitude as it was stopping me working, but that’s not showing contrition about yourself is it.4

I guess you could say it’s like the sacrament and receiving the Eucharist, its sort of eye opening to see your faults on paper. Then you can deal with them I guess. My son writes a diary, it’s sort of the same really isn’t it?

Newly inspired, CareCo employees ‘welcomed’ complaints and rejoiced at their ability to accept and learn from their failure – everything became a learning event, especially the penance usually increased workloads. Performance appraisal thus embodied revelation and redemption and brought the personal and organisational into the intimate. Here CareCo’s managers could be seen as a:

partner who is not simply the interlocutor but the authority who requires the confession, prescribes and appreciates it, and intervenes in order to judge, punish, forgive, console. (Foucault 1981:61)

The sinister development this represents is towards a situation in which even one’s failure, the touchstone of one’s humanity, is appropriated by the organisation in its constant drive towards cost-reduction and improved performance. Not only this, but also that for a confession to be effective it must be voluntary and freely made. Confessions are a response to what Gutman (1988:106) calls a “triumvirate of compunction, external gaze and the need for complete disclosure”. While performance appraisal’s examination and judgement are supposedly objective and value free, they irresistibly conjure up visions of the Grand Inquisitor (Paden 1988).

While traditional approaches towards performance appraisal have been predicated upon the ‘supremacy’ of the subject – the individual – acted on by various practices and dominant groups, the use of a subjective analysis implies that all are implicated in the process of subordination. At CareCo we have seen that the forms of knowledge and power were not discreet they were part of an overt discourse – that of quality – which moulded morality, sexuality, presentation of self and purity (re: quality) of thought for CareCo. The use of performance appraisal, rather than an end in itself, can be seen at CareCo as a ‘will to knowledge’, or power, over the individual (Foucault 1974). The analysis illustrates that the attempts by CareCo to affect individual forms of appearance and conceptions of self constituted the individuals as subjects in a pre-defined, ‘CareCo’, likeness. Thus Foucault is essential to tease out the underlying practices, which informed the notion of performance appraisal at CareCo, and drove its engine towards the subsumption of those professions within. All without performance appraisal proving its abilities to physically improve output or individual.

CareCo used performance appraisal in order that individuals adopt the correct attitude to the increased discretion and responsible autonomy that the introduction of a market (business) mentality brought. The replacement of work rules and supervision at staff level with discretion is a key feature of the dominant HRM model, which propounds this new kind of employment contract (Graham 1988; Guest 1989), but leaves little actual freedom. As such, CareCo’s new apparatus of control could be argued to lead to a more pernicious and coercive pattern of management for employees, through the direct attempt to manage meaning, identity and sexuality. Physical performance appears to be lost. CareCo’s movement towards the management of identity is adopting a different ideology all together, focusing on assessment of the internalisation of Trust goals and norms as an index of identification with the job and the hospital.

It would be disingenuous to argue that performance appraisal has become fully internalized by CareCo employees, however, the data does illustrate that it has made headway in this respect. Employees spoke of the need to act in a ‘quality’ way and to put the organisations first, employees always took ownership for any failures during appraisals. This could be due to the emotive nature of hospitals where “sloppy” work causes loss of life. Despite this they did voice issues, which might be construed as resistance – the questioning of the use of an image consultant.

However, the problem of control at CareCo appeared to be resolved by the personalising of the employment contract. By giving women appraisal records by which they can judge themselves and the organisation, CareCo has uncovered the means to elicit the commitment and internalised loyalty of its employees. The appraisal records were used as a way of impressing on individuals that their identity either reflected or refuted CareCo’s. With this CareCo had a very powerful mechanism of control through which it could appeal to women’s sexuality, loyalty and commitment. Hence the data pointed towards the belief that substance – measurable performance/output – was replaced with rhetoric and adoption of CareCo’s identity.

This is doubly important for the identity of women at CareCo with a majority of women staff. Sexuality and its attendant presentation became an essential part of the performance appraisal process. Performance appraisal was used as a means to assess femininity and to control those who sought to overstep the bounds of acceptable action and to weed out those not internalising a CareCo identity. Here individuals adopted the identity of CareCo or their jobs were ‘lost’ in a reshuffle.

There is an irony that as CareCo places more emphasis on competitive performance and quality (care) through an individualising practice such as performance appraisal, it seeks to turn its employees into mirror images of itself. As performance appraisal becomes more widely practised in the public sector, there is increasing need to critically unravel its implications and consequences in the pursuit of contemporary management practice.5

The Trust comprises four centres and gained trust status in April 1993.

Main Services

What follows is an approximation of the PA form used at CareCo. Certain questions have been altered/omitted in case they identify the institution.

1. Outline the main duties and responsibilities of your job during the past year and estimate the percentage of time that is taken up by each of your principle duties. (You may wish to complete a weekly diary profile for one or more weeks.)

2. Please indicate nature and extent of administrative duties, including committee membership.

3. Please give details of how you have met your objectives of the past year.

4. Please give details of any difficulties you have encountered and how you overcame them.

5. Please give details of external contacts and activities.

6. Please give brief details of consultancies (i) currently held (ii) in prospect.

7. Please give details of any other professional activities undertaken, (e.g. short courses, visits overseas and services to professional bodies), and why they were of benefit to you and to CareCo.

8. Please give details of staff development activities undertaken during the year

9. Please comment on the activities of the past year

10. Please comment on next year’s planned activities

1. Report on performance over the appraisal period

2. Agreed points for action to be taken by member of staff and by the Department

3. Support and training needs for carrying out the agreed action

4. Agreement on comments & action plan

PART 3 TO BE COMPLETED BY APPRAISEE WITHIN 14 DAYS OF THE APPRAISAL INTERVIEW

I have read the comments made by the appraiser and

(a) I have nothing further to add

(b) I wish to add the following

[Please delete (a) or (b) as appropriate]

These questions were also supplemented by a ‘score card’ marked by the appraiser on a scale of 1 to 5 during the discussion phase that occurred before the appraisers’ comments were written down.

Abe, E., Gourvish, T. (eds.) (1997) Japanese Success? British Failure? Comparisons in Business Performeance Since 1945. Oxford : Oxford University Press.

Ball, S. J. (ed.) (1990) Foucault and Education: Disciplines And Knowledge. London : Routledge.

Bartol, K. M., Martin, D. (1991) Management. New York : McGraw-Hill.

Bevan, S., Thompson, M. (1991) ‘Performance Management at the Crossroads’, Personnel Management, Pp36-40

Causer, G., Jones, C. (1996) ‘Management and the Control of Technical Labour’, Work, Employment and Society, 10(1):105-123

Chandler, J., Bryant, L., Bunyard, T. (1995) ‘Women in Military Occupations’, Work, Employment and Society, 9(1):123-135

Coates, G. (1992) ‘Presenting A Single Face: Understanding Workplace Commitment Through Social Interaction’, Paper Presented to the 10th Standing Conference on Organisational Symbolism, Lancaster.

Coates, G. (1994) ‘Performance Appraisal : Oscar Winning Performance or Dressing to Impress?’, International Journal of Human Resource Management, 5(1):167-192

Cockburn, C. (1985) Machinery of Dominance : Women, Men and Technical KnowHow. London : Pluto.

Collins, H. (1992) The Equal Opportunities Handbook. Oxford : Blackwell.

Cotton, J. L. (1993) Employee Involvement: Methods for Improving Performance and Work Attitudes. London : Sage.

Cutcher-Gershenfeld, J., Nitta, M., Barrett, B. (1998) Virtual Knowledge : The CrossCultural Diffusion of Japanese and US Work Practices. Oxford : Oxford University Press.

Cutler, T. (1992) ‘Vocational Training and British Economic Performance’, Work, Employment and Society, 6(2):161-183

Elger, T. (1990) ‘Technical Innovation and Work Reorganisation in British Manufacturing in the 1980’s’: Continuity, Intensification or Transformation?’, Work, Employment and Society, 4(Special Issue):67101

Ferris, G. R., et al. (1991) ‘The Management of Shared Meaning in Organisations: Opportunism in the Reflection of Attitudes, Beliefs And Values’, in Giacalone, R. A., Rosenfeld, P. (Eds.) Applied Impression Management. London : Sage.

Foucault, M. (1974) The Archaeology of Knowledge. London : Tavistock.

Foucault, M. (1979) Discipline and Punish. Harmondsworth : Penguin.

Foucault, M. (1981) The History of Sexuality : An Introduction. Harmondsworth : Penguin.

Fox, A. (1985) Man Mismanagement. London : Hutchinson.

Gold, R. L. (1958) ‘Roles in Sociological Field Observation’, Social Forces 36:217-223

Graham, I. (1988) ‘Japanization as Mythology’, Industrial Relations Journal, 19(1):19-25

Grey, C. (1993) ‘A Helping Hand: Self-Discipline and Management Control’, Paper Presented to the 11th Labour Process Conference, Blackpool.

Guest, D. (1989) ‘Human Resource Management: its Implications for Industrial Relations and Trade Unions’, In Storey, J. (Ed.) New Perspectives on Human Resource Management. London : Routledge.

Gutman, H. (1988) ‘Rousseau’s Confessions : A Technology of The Self’, In Martin, L., Gutman, H., Hutton, P. (Eds.) Technologies of the Self : A Seminar With Michel Foucault. London : Tavistock.

Harley, S., Lee, F. (1995) ‘Control Surveillance and Subjectivity : The Research Assessment Exercise, Academic Diversity and the Future of Non-Mainstream Economics in UK Universities’, Paper Presented to the 13th Annual Labour Process Conference.

Hearn, J., Parkin, W. (1987) ‘Sex’ at ‘Work’. Brighton : Wheatsheaf.

Hill, S. (1991) ‘How do you Manage a Flexible Firm? The Total Quality Model’, Work, Employment and Society, 5(3):397-416

Hochschild, A. (1983) The Managed Heart : Commercialization of Human Feeling. Berkeley : University of California Press.

Keating, P., Witkin, R. W. (1992) ‘Culturally Mediated Employee Responses to the Implementation of Managerial Techno-Culture in the Banking Industry’, Paper Presented to the BSA Conference, Kent.

Kramer, L. (1989) ‘A Guilty Plea Confirms the Dark Rumours About Capitol Hill Aide Quentin Crommelin’, People Magazine, 21, August 49-50

Littler, C. R., Salaman, G. (1982) ‘Bravermania and Beyond: Recent Theories of the Labour Process’, Sociology, 16:251-268

McArdle, L et al. (1992) ‘Managerial Control Through Performance Related Pay’, Paper Presented to the 10th Annual Labour Process Conference Aston.

McGregor, D. (1960) The Human Side of Enterprise. New York : McGrawHill.

Miller, H. (1991) ‘Academics and Their Labour Process’, In Smith, C. et al. White-Collar Work: The Non-Manual Labour Process. London : Macmillan.

Molander, C., Winterton, J. (1994) Managing Human Resources. London : Routledge.

Morgan, G. (1990) Organizations in Society. London : Macmillan.

Murphy, K., Cleveland, J. (1995) Understanding Performance Appraisal : Social, Organisational, and Goal-Based Perspectives. London : Sage.

Paden, W. (1988) ‘Theatres of Humility and Suspicion : Desert Saints and New England Puritans’, In Martin, L., Gutman, H., Hutton, P. (Eds.) Technologies of the Self : A Seminar With Michel Foucault. London : Tavistock.

Pulkingham, J. (1992) ‘Employment Re-Structuring In The Health Service: Efficiency Initiatives, Working Patterns And Workforce Composition’, Work, Employment and Society, 6(3):397-422

Pym, D. (1973) ‘The Politics and Rituals of Appraisals’, Occupational Psychology, 47:231-235

Rabinow, P. (Ed.) (1986) The Foucault Reader. London : Peregrine.

Ramsey, H. (1991) ‘Reinventing The Wheel? A Review of the Development of Performance and Employee Involvement’, Human Resource Management Journal, 4(1):1-22

Reed, M. (1989) The Sociology of Management. Hemel Hempstead : Harvester Wheatsheaf.

Reed, M. (1992) The Sociology of Organisations. Hemel Hempstead : Harvester Wheatsheaf.

Reed, M., Whitaker, A. (1992) ‘Organisational Surveillance and Control Under Re-Organised Capitalism: Managerial Control Strategies and Structures in the Era of Flexible Fordism’, Paper Presented to the 10th Annual Labour Process Conference, Aston.

Rees, G., Fielder, S. (1992) ‘The Services Economy, Sub-Contracting and New Employment Relations: Contract Catering and Cleaning’, Work, Employment and Society, 6(3):347-368

Rohlen, T. P. (1980) ‘The Juku Phenomenon’, Journal of Japanese Studies, 6(1):25-37

Sewell, G., Wilkinson, B. (1992) ‘“Someone to Watch Over Me”: Surveillance, Discipline and The Just-in-Time Labour Process’, Sociology, 26(2):271-290

Shamir, B. (1990) ‘Calculations, Values and Identities: The Sources of Collective Motivation’, Human Relations, 43:313-332

Sims, D. Et Al. (1993) Organising and Organisations : An Introduction. London : Sage.

Strauss, A., Fagerhaugh, S., Suczek, B., Wiener, C. (1982) ‘Sentimental Work in the Technologized Hospital’, Sociology of Health and Illness, 4(3):254- 277

Sturdy, A. et al. (1992) Skill and Consent: Contemporary Studies in The Labour Process. London : Routledge.

Tolliday, S., Zeitlin, J. (Eds.) (1991) The Power to Manage. London : Routledge.

Townley, B. (1994) Reframing Human Resource Management : Power, Ethics, and the Subject at Work. London : Sage.

Truss, C. J. (1993) ‘The Secretarial Ghetto : Myth or Reality? A Study of Secretarial Work in England, France and Germany’, Work, Employment and Society, 7(4):561-584

York, G. (1989) ‘Judge Offers an Apology for Comment on Slapping’, The Globe and Mail, 23, September.

1. For example, the use of temporary contracts in higher education is important in the removal, for academics, of a subtle freedom to plan their career with any certainty.

2. All names used herein are pseudonyms and some details have been purposefully omitted to protect its identity.

3. The event cannot be reported here as a legal action is still being fought.

4. The author, in promising confidentiality cannot illustrate the form here. See appendix 2 for an approximation.

5. In 1995 the speaker in the House of Lord spoke out against PA on the grounds that services could not be objectively measured.

Copyright 1999 Electronic Journal of Sociology