Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Milan Zafirovski University of North Texas

The equation of human rational behavior with instrumentalist, especially economic, rationality represents the hallmark of the economic or rational choice approach. The latter imports, makes explicit and extends orthodox economics’ implicit conception of rational behavior as economic rationality. This orthodox conception defines economic rationality by maximization of exclusively materialist objectives, namely profit by producers and utility by consumers. The rational choice approach then explicitly applies this conception to all rational and human behavior that is thus construed as ipso facto economic rationality. The paper argues that the rational behavior of human agents is far from being invariably utility- and profit-optimizing, and thus cannot be automatically reduced to economic rationality. The main argument is that behavior can be rational not only on economic grounds but also on non-economic ones. Hence human behavior can be non-rational in economic and yet rational in extra-economic terms, i.e. economically irrational and non-economically rational.

The purpose of this paper is to critically reexamine the prevalent notion of rational behavior within mainstream economics and rational choice sociology (for a recent general critique of rational choice theory, see Archer and Tritter 2000). The paper tries to demonstrate that this conception is both theoretically and empirically inadequate. The paper proposes an alternative conception that transcends or greatly relaxes the instrumentalist, especially economistic, notion of rational behavior, and thus contributes to a more satisfactory framework for approaching this matter. Most generally, rational behavior is defined by a necessary, natural or logical association or adaptation between ends and the means for their attainment, as the Pareto notion of logical conduct, as equivalent to Weber’s of aim-rational or goal-oriented action, implies (Boudon 1982). Such an association characterizes subjective, constrained or bounded rational behavior (Simon 1982) to the extent that the association is perceived by the actor as logical, instrumental or functional to attaining the ends sought whatever these may be. In other words, a given course of action would generally represent rational behavior insofar as agents have good reasons or rationale for such actions (Boudon 1989).

On the other hand, the means-end association also leads to objective rational behavior insofar the alters or observers, alongside the ego, regard the association as logical or functional i.e., as induced by definite goals, reasons or meanings, which they can understand in the sense of Verstehen or empathy, though not necessarily approve or sympathize with. As such, rational behavior in general is determined by a certain relevant degree of coherence between the subjective meanings or good reasons of the actor and the objective purposes attributed by other actors and/or observers. This implies a proximate but essential equivalence in the ex ante or ex post teleological specification of action between the actor and the social environment, which does not rule out various dis-junctures between actions that are subjectively rational by their good reasons and objectively rational or, as Weber puts it, correct by their demonstrated or externally imputed purposes. In short, rational behavior as perceived or experienced by the actor is not necessarily what is observed or attributed by the other actors, and vice versa (Boudon 1982; Simon 1982).

Hence, social behavior devoid of such properties, viz., the logical association between ends and their means, would evince non-rationality or non-logicality, albeit not necessarily irrationality or illogicality, just as, for that matter, any human conduct, rational or not, can display amorality but not immorality. Such incidence of non-rational behavior is not affect by the tendency of humans to, paint in Pareto’s words, a “varnish of logic”, reason or rationale over their objectively or externally observed non-rational or unreasonable actions in that they resort to derivations or rationalizations, including personal ideologies, to make such actions appear rational or reasonable.

However, what is at stake at this juncture is not the question of the incidence and pertinence of rational behavior in social life or of the possibility for constructing a sociological theory of rationality as well as non-rationality (Boudon 1982). Instead, the problem to be addressed pertains to building a proper conception of rational behavior as such, viz., to defining what rational behavior is in the context of social action and social structure1 . For the sake of accomplishing this, the paper has the following outline. Section I identifies a teleological fallacy of purpose determination in current economistic or hard-core conceptions of rational behavior and proposes a corrective. In section II the claims that the economic or rational choice approach is the only and best unified model of human behavior are scrutinized and alternative non-rational models intimated. Also reconsidered in section III are the claims that rational choice really represents a unified model by pointing to the underlying tension between parsimony and realism. Section IV classifies alternative strategies for substantive theory construction in sociology based on the assumed importance of rational behavior. Section V re-examines the possibility that soft or thick conceptions of rational behavior are more satisfactory than their hard-core or thin counterparts. The paper concludes with summing up the comparative properties of the prevalent conception of rational behavior and its alternative.

The above preliminary definition of rational action implies no specification of the ends or means of it. They can be both economic and noneconomic, instrumental and noninstrumental, egoistic and altruistic, private and social, and so on. The conception of rational action does not prejudge or prescribe the underlying teleology, namely the character of the purposes or goals pursued. Because the necessary precondition for rational action is the existence of an inherent link between ends and means, whatever they may be, if this link is perceived as such by the actor (ego) and/or others (alter-ego). This contrasts to the curious tendency of rational action theory to define these purposes as a priori economic, instrumental, egoistic and private, such as utility, profit, or wealth optimization, rent-seeking, cost minimization, cost-benefit calculation, and the like, and thus to restrict all of them to a single class. The underlying assumption of this procedure is that only such goals and the corresponding actions, means, and choices are rational, and others nonrational or even irrational.

Reminiscent of the old utilitarianism, modern rational choice theory in sociology and economics defines rational behavior as ipso facto rational in instrumental terms, as economic rationality or utilitarian calculation. Subsuming all the ends, reasons, and motives of action to instrumental, egoistic or hedonistic ones, i.e., pursuit of utility, self-interest or pleasure, and avoiding disutility and pain do this. Thereby, a particular form of rationality, viz. instrumental, utilitarian, egotistic, or hedonistic2 , is conflated with rational behavior as a whole. Conceptually, this procedure is predicated on the assumption of “rational egoism”3 (Hechter and Kanazawa 1997) and leads to pan-utilitarianism or economic imperialism through expanding the principle of utility optimization, often conjoined with the concept of market equilibrium, to all social life4 . In sum, the “assumptions of utility maximization and equilibrium in the behavior of groups [are] the traditional foundations of rational choice analysis and the economic approach to behavior” (Becker and Murphy 2000:5).

I try to show that rational choice analysis and/or the economic approach, premised on a definition of rationality as utility maximization, logically flawed and empirically invalid. First and foremost, it commits the fallacy of sociological reductionism by dissolving all types of social action, including rational conduct, into a single type of instrumental behavior exemplified in utility maximizing (Alexander 1990; Barber 1993). Hence, I make an argument for going beyond optimizing utility (Slote 1989), thus transcending the instrumentalist conception of rational behavior (Gerard 1993), to a more powerful and broader notion of rational behavior than maximization (Bonham 1992) and even satisficing with respect to utility or bounded-rationality theory. In short, what is needed is admittedly an “open theory of rationality rather than the special [closed] figure of rationality used by [rational choice theory]” (Boudon 1998:824).

Unlike neoclassical economics and sociological rational choice theory seeking its generalization (Rambo 1999) and extension (Macy and Flache 1995) to non-economic phenomena, an alternative approach to social action includes both rational or instrumental and “non-rational choice theory dimensions of rationality” (Boudon 1998:824). Hence, in this approach rational social action is a rich and complex category transcending instrumental or economic rationality as just one of its elements. It is so untenable to dissolve the former into the latter as done by current rational choice theory, with its overemphasis on the rigid and narrow (Boudon 1996) conception of rational behavior borrowed from neoclassical economics and then indiscriminately extended.

In general, sociological rational choice theory (Kiser and Hechter 1998; Hechter and Kanazawa, 1997) or rational action theory for sociology (Goldthorpe 1998) does no more than “simply takes narrow neoclassical themes to perform in other arenas’ (Ackerman 1997:662). While developing to a degree independently of economics, sociological rational choice theory has become the “most striking example of the use of economic reasoning within sociology” (Kalleberg 1995). In turn, the rational choice model rejects most assumptions of traditional sociology and seems inconsistent with much of classical sociological theory, including Weber’s.

For illustration, Coleman’s rational choice theory is admittedly “based on a generalization of general economic equilibrium theory”5 (Fararo 2001:272). In this sense, rational choice theory appears admittedly parasitic (Coleman 1986; Elster 1989; Fararo 2001)–despite some recent qualifications and distancing (Coleman 1994; Goldthorpe, 1998; Hechter and Kanazawa, 1997)–in relation to its “neoclassical cousin” (Kiser and Hechter 1998) rather than an autonomous emerging paradigm or nascent research program (Abell 2000; Kiser and Hechter 1991). The procedure of dissolution commits what can be termed the fallacy of misplaced abstractness or generality, because it illegitimately equates the particularity of a component, namely instrumental rationality, with the universality of the whole, rational behavior. All this involves various simplifications, conflations, reductions, and confusions in regard to the categories involved, particularly instrumental and other types of rational behavior, as well as formal and substantive rationality, objective and subjective rationality, immediate and long-term rationality, and so on.

The principal differences between conventional rational choice theory and a more plausible alternative are outlined as follows. While the former assumes that rational choice is or should be only a narrow instrumental or economic choice–utility, profit or wealth maximization– the latter argues that choice can also be a non-instrumental choice, the pursuit of well-defined objective functions or goals, such as power, prestige, justice, religious happiness, ethical perfection, ethnical identity, ideological purity or aesthetical pleasure. A broader theory posits that the second type of rational behavior is not reducible to the first, rejecting thus the typical reductionism of a narrow rational choice theory that dissolves everything into utility and egoism. No wonder, the utility function has become almost meaningless, covering everything and so nothing specifically, as a result of which rational choice theory becomes a putative theory of everything (Hodgson 1998:168), which thus “simultaneously explains everything and therefore nothing” (Smelser 1992:403; also Ackerman 1997:663). Even some rational choice theorists are unhappy with this situation, complaining that no empirical content has remained in the utility function ostensibly maximized by the economic man. The utility function has become a convenient device, especially a mathematical trick, by virtue of treating rational behavior as optimizing or satisficing with respect to utility Admittedly, it is highly implausible to define rational social action as maximizing some utility function (Margolis 1982:16). The basic assumption of the economic approach to human behavior or instrumental rational choice theory that actors are rational utility maximizers in their economic as well as social behavior–i.e., in all of their behavioral capacities (Buchanan 1991:29-36)–can be treated as deprived of real content or ontological meaning. For more often than not it is virtually impossible to demonstrate its empirical (in)adequacy (Lea 1994:71-5).

For instance, as to the observance of social norms, narrow rational choice theory assumes that this process is grounded on consistent cost-benefit calculations by rational egoists (Hechter 1990). On the contrary, the broader version postulates a definite set of various factors or possibilities in this regard, of which the instrumental is just one. Purely disinterested respect for social norms can often be the principal motivation for normative conformity, in conjunction with prestige that it breeds, irrespective of the direct profit (Bourdieu 1988:19-22) associated with this behavior. Actors do not always follow social norms because of instrumental or economic considerations, but also because of non-instrumental ones, expressed in the internalization of norms as an autonomous process not contingent on profit-loss computations. Such instrumental considerations are of secondary importance, since no utility or other extrinsic reinforcements are maximized by the non-rational non-instrumental decisions involving consideration of internalized rules and values (Marini 1992:37) and other intrinsic motivation, as even some economists admit (Kreps 1997). In general, social action can be treated as guided by economic rationality as well as by normative considerations rather than either by the former, as assumed by rational choice theory–and, for that matter, by vulgar dialectical materialism–or by the latter, as posited by culturalist conceptions.

The common point of both narrow and broader versions of rational choice theory is the postulate of universality of rational behavior in human society. But the differentia specifica or comparative advantage of instrumental rational choice theory, contrary to the assertions of its exponents, is not that it alone, unlike other sociological theories such as functionalism, assumes and allows rational behavior in social life. Rather it is solely in that such a rational choice theory reduces this choice to its narrow instrumental variant. To argue that rational behavior is universal in society is not equivalent to saying, as rational choice theory does, that this choice is necessarily of such a limited character. And if one assumes, by applying the charity principle of rational behavior (Elster 1979:116-7), that instrumental choice is ubiquitous in social life, the same can be posited for social values and norms–e.g., habits and other cultural rules are “ubiquitous’ in human action (Hodgson 1997:663)–defining and expressing the “patterned principles of these choices’ (Barber 1993:359). Hence, it seems to some economists that “neither neoclassical nor behavioural economics can provide a complete account of the bases of habits or rules’ (Hodgson 1997:663).

Furthermore, instrumental rational behavior, viz. Weber’s zweckrational action, can be influenced or overruled by non-instrumental rational behavior, i.e. the idealistic rationality of absolute values (Alexander 1990) or value-laden rationality as a distinct type of rational behavior not reducible to the first type. This is because, given the existence of the social and historical factors of value formation, in a sociological analysis values cannot plausibly be regarded as ordered utilities (Willer 1992:57-59). The usual public-choice reduction of political action to economic action–for instance, power to wealth, democracy to market competition, electoral processes to business cycles, and the like–is equally inadmissible. Because by involving coercion or conflict, in contrast to economic relationships in a market economy as presumably voluntary ones, power and other political relations pertain to the level of action within the province of a distinct social theory, and are so not reducible to the rational choice theory level (Munch 1992:139-41). This non-reducibility of political power to wealth or economic power is justified at least by the fact that, in Parsons’ words, the former is hierarchical and qualitative, and the latter linear and quantitative. Even some rational choice theorists concede that market power or wealth is distinct from political power, albeit this latter can be achieved inter alia by the former (Coleman 1986:281-3).

This is precisely what most contemporary economists and rational choice theorists are prone to do, by dissolving all social actions, values, and goals to mere instrumental categories. This approach is exemplified by the typical rational choice reduction of altruism and so value-rational action to an inverted form of egoism and instrumentally-rational action. However, by treating altruistic behavior as being propelled by self-interested motives rational choice theory amounts to a self-contained or rather self-defeating and/or self-effacing explanation6 (Sugden 1991). No wonder, such a reduction has been rejected by some moderate rational choice theorists (Boudon 1998; Elster 1998). On this account, one may even suggest that an adequate rational choice theory in sociology can be built only by transcending the stringency of the assumptions of the economic approach (Willer 1992). Thus, the narrow instrumental conception of rational behavior based on such assumptions is to be substituted by a broader one allowing instrumental and non-instrumental, instrumental and non-instrumental, including axiological and cognitive rationality7 (Boudon 1998). Admittedly, social life is hardly ever fully utilitarian, and people do not actually optimize utility through consistent and precise cost-benefit calculations (Homans 1990:77).

Therefore, rational behavior can include not just purely instrumental ends, such as utility, profit or wealth, but also social ones–action is rational if it aims “not only at economic goals but also at sociability, approval, status, and power” (Granovetter 1985:509-10). It is a fundamental fallacy of modern rational choice theory to subsume all these ends of action to just one type (the economic), through tortuous reasoning that makes the latter ostensibly universal but theoretically meaningless and empirically useless (Knoke 1988). In doing so, it grossly overlooks the fact that not only material but also ideal interests may constitute the basis of rational social action, including even economic action, as classically demonstrated by Weber. In this context, Weber’s distinction between value-rational action driven by ideal interests, such as religious, political, ethical or ideological values, and affective action prompted by emotions–as well as Pareto’s between logical and non-logical actions caused by interests and residues respectively– appear fluid. This holds true of the distinction between value-rational action and instrumentally-rational social action seen in turn as motivated by material interests.

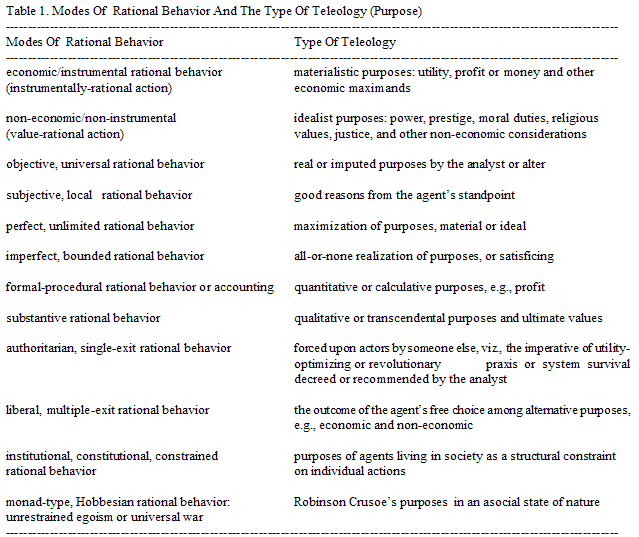

Therefore, these interests by no means exhaust the motive factors of rational social action, including its economic modes. This implies that economic rationality and the economic system is far from being self-referential vis-à-vis rational behavior and the social system as a whole. Rather instrumental or economic choice is just a subcategory of rational behavior that can be also non-instrumental or non-economic one. Not all rational social actions can be reduced to economic actions or principles, as Weber has classically argued. This reduction has been viewed with suspicion not only by anti-utilitarian classical sociologists, except, say, Spencer, but also by many (neo)classical and contemporary economists, from Mill and Jevons and Walras to Pareto and Marshall to Schumpeter and Keynes. Notwithstanding, this reduction is typically performed by the economic or rational choice approach to human behavior. The preceding discussion indicates the reality and salience of a plurality of rationalities in human social behavior in light of the teleological or purpose multiplicity, not a monolithic economic-instrumental–and, for that matter any other–rational behavior predicated upon a single purpose like utility, as assumed by rational choice theory. Table 1 summarizes these plural modes of rational behavior in relation to such a teleological multiplexity in social life.

Rational choice theorists typically make suggestions and claims for a single, unified model rather than many different models of human behavior. In particular, the claim is made that one cannot have two or more different models of the same actor and therefore of the identical human behavior, but rather one—and this is the model of rational choice. However, the question arises as to whether rational choice is really the only or at least the best unified model or general theory of social action. Alternatively, the question can be rephrased to the effect of whether theories of non-rational behavior can also represent a unified and perhaps more adequate model of social action than their rational counterparts. This question is addressed next by reconsidering the arguments for and the types of non-rational unified models of social action.

The argument for unified non-rational models of social action, i.e. general theories of non-rational behavior, can be grounded on their epistemological and ontological legitimacy. In terms of epistemological legitimacy, there is no . priori reason for adopting unified rational models of social action and rejecting their non-rational counterparts. Non-rational unified models of social action are not necessarily less methodologically legitimate than rational ones. Just as it is legitimate to argue that human behavior is “always and everywhere rational”, so is it to assume that it is mostly non-rational and even irrational in economic-utilitarian terms. For instance, a unified model of non-rational social action in terms of habits and institutions (Hodgson 1998) is admittedly (Arrow 1994) as methodologically legitimate as one of strictly rational conduct, viz. “generalized calculus of utility maximizing behavior” (Stigler and Becker 1977). Perhaps more importantly, non-rational unified models of social action are not invariably less ontologically legitimate or empirically sound than rational ones. Moreover, non-rational unified models of human behavior can be superior to their rational equivalents in terms of ontological legitimacy or empirical relevance insofar as social, including even economic, life is—as admitted even by some neoclassical economists–“ontologically irrational” (Schumpeter 1991:337). At least, it is admittedly, in Pareto’s terms, non-logical, at least or quasi-rational (Thaler 1994).

Having established their epistemological and ontological legitimacy, unified non-rational models of human behavior can generally be classified in the following groups. One group includes unified models of value-laden behavior. Cases in point are, for example, Weber’s concept of value-rational (wertrational)—i.e. non-economically rational and yet economically non-rational—action induced by the ethic of absolute ends, viz. the ideal type of Protestant capitalist entrepreneurs, then Pareto’s homo religiousus (Schumpeter 1991:336), etc. Another, related group involves unified models of what Weber calls “rule-governed behavior”. Instances of such models of the “rule-governed aspect” (Hayek 1991:368) of human behavior are Weber’s concept of traditional action, Veblen’s of habitual or customary conduct, as well as Durkheim’s of moral agent, and the like. Included in still another group of unified non-rational models are those of emotional and expressive behavior. Such models are exemplified by Weber’s type of affective action, Pareto’s notions of residues (sentiments) and derivations (rationalizations), viz. what neoclassical economists like Wieser term the “joyful power to create” for its own sake or the “joy of creating” (Schumpeter 1949:93) and various Keynesian “animal spirits’ reflecting a non-hedonistic psychology of economic agents, including entrepreneurs.

A next group incorporates unified power models of behavior, which acknowledge that people often seek power or domination not just for as a means to economic ends, but, in Weber’s words, “for its own sake”. The Weberian conception of power, domination and authority is an example of–or at least is conducive to building–such unified non-rational models. Moreover, a unified power, hence non-economically rational and economically irrational, model of human behavior can be ontologically more adequate than its economic or rational equivalent to the extent that the pursuit of materialistic ends admittedly “pales in innocence” (Mueller 1996:346) by comparison to seeking power. A distinct class of unified non-rational models of human behavior involves those premised on the quest for social status or group approval (Frank 1996). A case in point is Veblen’s conception of seeking prestige through a wide range of activities, e.g. conspicuous consumption, leisure, education, etc., as well as Weber’s notion of status groups differentiated on the basis of social honor. And, rather than being a mere instrument of wealth maximization as the “typical value assumption” of the rational choice model (Hechter 1994), social status is often the primary or ultimate goal of social, including economic action, with wealth becoming a means to that goal. Also, unified institutional-historical models of human behavior can be deemed a distinct class in the above sense. These models can be epitomized by or based on Durkheim-Weber-Parsons’ conception of institutional motivation, preferences, and individualism, Veblen’s of the bearing of institutional evolution on individual behavior, the Historical School’s of the social-cultural specificity of economic activities, and so on.

The preceding suggests that, contrary to the claims by rational choice theorists, there are no valid epistemological or methodological and ontological or empirical reasons why a unified model of human behavior should be of a rational type only. Rather, non-rational and even irrational unified models do exist or can be built in the same right as their rational equivalents. In epistemological terms, both types of unified models are equally legitimate to construct—no sensible methodological argument can be invoked for rational-only models and against non-rational ones. At this juncture, rational choice theorists’ invocation of the “charity principle” of presumptive rationality–“actors are probably rational”–is no more legitimate than turning the principle on its head in the form of an assumption of non-rationality that “life is irrational” or at leas quasi-rationality. In short, to claim that rational choice is the only available, possible or the best unified model of human behavior is methodologically implausible. In ontological terms, rational and non-rational unified models of human behavior are both legitimate to the extent that they have some pertinent degree of empirical validity. Hence if unified non-rational models do justice to some relevant aspects of the reality of social action, they are ontologically as legitimate as rational models, charitably assuming that these also do so. Furthermore, the claim that rational choice is the best and only unified model of human behavior can be rejected on empirical grounds in favor of a unified non-rational model insofar as observation and systematic evidence indicate, as hinted above, ontological non-rationality rather than rationality (Schumpeter 1991:336-7). In this connection, it is instructive to note the peculiar and somewhat unexpected path of many broad-minded economists as well as sociologists, e.g. Marshall, Pareto, Schumpeter, Parsons, Weber. This is the path from the initial epistemology of rationality—i.e. what Weber termed rationalistic method–to the eventual ontology of non- or pseudo-rationality. In other words, the path starts from the assumption of rationality in social action, and ends with some kind of serendipitous discovery of the factual prevalence of non- or quasi-rationality, which was, incidentally, instrumental in many economists’ conversion into sociologists, such as Pareto, Parsons, Weber, etc. Nevertheless, contemporary rational choice theory while starting from the same rationality assumption or the charity principle has not yet reached this “discovery” despite some hints in this direction (Boudon 1998; Elster 1998).

In addition, the very argument for a single, unified model—rational or non-rational–of human behavior can be questioned. Insofar as both rational and non-rational unified models involve seemingly parsimonious and yet discredited single-cause explanations, they commit the fallacy of theoretical monism. Particularly, such a fallacy suggests the need for reexamining if not rejecting (Hirschman 1984) the parsimony rule itself. Thus, those models that are multidimensional, more complex and provide more realistic explanations are to be preferred to those one-sided, simplistic, parsimonious and unrealistic8 . Thereby, theoretical pluralism is preferred over monism, given the complexity and multiplicity of the real world (Arrow 1997:765). The claim that rational choice is a unified model as such is reexamined next.

Not only can the claims that rational choice is the only and best unified model of action can be questioned, but also the very claim that the model is unified, i.e. internally coherent. As mentioned before, the standard rational choice justification of a unified model, i.e. a general theory, of social behavior is that one deals with the “same actor” whether analyzing action in the market-economic realm or in the non-economic sphere. Ostensibly, rational choice provides such a single model on the grounds that the presumption of universal rational behavior, by applying the rationalist charity principle of interpretation of social behavior, is well-grounded in reality. However, upon inspection rational choice reveals a paradoxical itinerary directly or indirectly contradicting and weakening the unity and coherence of the model. In general, this is the itinerary from an ostensibly unified model of social action to several different, explicit or implicit, models of it. The more particular instances of this curious trajectory are noted below.

(a) From a “comprehensive economic approach to all human behavior” (Becker 1976:3) explaining “not only ordinary market behavior [but] also implicit [social] markets’ (Becker and Murphy 2000:5) to one model of egoism for actions in the market economy and another model of altruism for conduct within the family, viz. marriage or parents-children relations and related non-economic domains (Becker 1991; Demsetz 1997). One wonders whatever happened to the initial single model of all human behavior in this attempt at greater realism and complexity via ad-hoc assumptions, such as altruism though this is construed as an inverted form of egoism, at the expense of parsimony, simplicity and unique explanation/prediction.

(b) From a universal model of instrumental/utilitarian values and reasons, viz. wealth maximization, cost-benefit calculation, to one special model for zweckrational instrumental values and actions and the other for wertrational or non-instrumental, including immanent, ones (Boudon 1996; Hechter 1994; Goldthorpe 1998; Kiser and Hechter 1998). For example, the one is sometimes termed the rational choice or cost-benefit model in the strict sense and the second the axiological or cognitivist model (Boudon 1998). Again, one wonders whatever happened to the original single model of human behavior or general social theory (Abell 2000) based on instrumental-only variables after this ad-hoc proliferation of two apparently different models for the “same actor.”

(c) From a single model of individual rational choice to two different models: one for rational agents and behaviors in economic terms and another for rule-following ones (Hayek 1991; Goldthorpe 1998). This is a curious path from an overarching principle of homo economicus assumed to be universally valid to its splitting into one for actors making private rational choices and the other for agents, following internalized social rules, instead. Simply, now homo economicus has become blended with homo sociologicus (Boudon 1981) in a curious mixture sometimes termed homo socio-(logicus) economicus. This actor concept might provide an empirically more plausible account of real-life actors and behaviors, but again the question arises whatever happened to that same and single actor–homo economicus making rational choices–with whom the rational choice model started. For now there seems to be one actor that makes consistently rational choices through accurate cost-benefit calculations and another that equally consistently engages in rule-governed behavior. While initially the single rational choice model presumed that agents followed social rules for cost-benefit reasons, now more complex models allow that rule-governed behavior or value-ridden cannot always be explained in terms of rational calculations (Boudon 1998; Hechter 1994), as Durkheim, Weber and other classical sociologists argued long time ago. Apparently, it took some time to modern rational choice theorists to finally in an ad hoc manner incorporate this crucial sociological argument and thus make their theory more realistic. Using rational choice terminology, this incorporation may produce greater benefits than costs, yet the cost is not insignificant insofar as not much is left from an initially unified model predicated on the proverbial same single agent, viz. “anemic, one-sided homo economicus’ (Bowles 1998:78).

(d) From a general rational choice model based on the cost-benefit principle to two different even opposed models: one retaining reasons for action of the cost-benefit type and the other including axiological, cognitive and related factors (Boudon 1996). Presumably, the first pertains to largely economic behavior, viz. zweckrational action, and the second to non-economic conduct, especially wertrational action. In a similar vein as the preceding, the outcome is some paradoxical—from the stance of the initial model–combination of homo economicus and homo sociologicus (Boudon 1981). No doubt, realism is thereby greatly increased, but through ad-hocism that apparently dissolved or changed beyond recognition the initial unified model that is seen with “pride and joy” by most rational choice theorists.

(e) From an overarching rational choice model resting on self-interest to its dissolution into one model of rational egoism and the other of morality, under the apparent influence of Adam Smith’s distinction between selfishness and moral sentiments, including sympathy (Lindenberg 1989). This implies a broader shift from a single model of economic incentives or materialistic ends (Mueller 1996) into two separate models for two classes of actors: one for those with extrinsic motives like profit or wealth, and the other for those with intrinsic motivation, including moral or civic duties (Frey and Oberholzer-Gee 1997). Again, the above may make the rational choice model more realistic, but through ad-hocism and at the price of disintegrating the original unified model predicated on the invariant pursuit of self-interest and other extrinsic incentives. Therefore, the initial same agent is now split into a rational egoist (Hechter and Kanazawa 1997), who knows the economic price of everything and the (non-economic) value of nothing, and a normatively (especially morally) as well as emotionally actuated actor (Etzioni 1999) acting—as even many economists recognize (Frey and Oberholzer-Gee 1997)–not just for profit or money.

The above suggests that rational choice finds itself between parsimony/deductive tractability and empirical plausibility/realism, i.e. between the Scylla of simplification and the Charybdis of ad-hoc complexity. One way out of this situation can be a rational-nonrational unified model of action as a corrective to rational-only and non-rational-only models alike. Such a unified model can be justified on epistemological and ontological grounds. As hinted earlier, the epistemological justification consists in that, methodologically, one can start with non-rational as well as with rational behavior, so the principle of non-rationality is not necessarily less legitimate in epistemological terms than that of rational behavior as most rational choice theorists claim. Ideally, both principles can be fused a unified rational/non-rational model of behavior, which while less parsimonious, tractable and more complex than either is to be prima facie preferred to each by virtue of its theoretical pluralism or multidimensionality just as, say, multiple regression analysis is to be chosen over simple regression in the cases of multiple variables and complex relations between them. In turn, the ontological rationale for a unified rational/non-rational model is provided by the observed fact that social, including even economic, behavior is complex characterized not only by rationality but also and perhaps more by non–rationality. The above suggests some alternative strategies for model building, especially substantive theory construction in sociology and other social science like economics, as discussed next.

In this section emphasis is on substantive theory construction, as distinguished from its formalization. In this connection, the relevance of substantive theory has often been asserted, even within neoclassical economics, by the view that substantive argument is essentially independent of its formal, including mathematical, representation9 (Marshall 1996), as has . fortiori within classical sociology10 (Pareto 1963). The possible strategies for substantive theory building in sociology can be classified according to various criteria, including rational behavior, individualism, institutionalism, etc. Using economic rationality as a specific criterion for classification, alternative strategies of substantive theory building involve general rational theories, general non-rational theories, and general mixed theories.

First, general rational theories are usually based on a single model and principle of rational behavior. In Weber’s terms, this is the model or conception of instrumentally-rational social action and of formal or economic rationality. In other words, the homo economicus principle is assumed to operate (e.g. by Austrian economists like Mises) not only in the economy, i.e. the production and consumption of material goods, but in all society conceived as an overarching market-place.

Alternatively, general non-rational theories rest on an overall model and principle of non-rationality. In a Weberian context, this model involves economically non-rational types of social action, viz. value-rational, traditional and emotional, as well as substantive or non-economic rationality. Hence, in analogy to the link of homo economicus and rational behavior, homo sociologicus represents the general principle or concept of economic non-rationality or non-economic rationality. Some particular principles or theories of non-rationality include (following the terminology of Schumpeter 1991:336-7) the following: a. homo religiousus, homo moralis, etc. expressing value-ridden action or substantive rationality; b. homo habitus as an expression of traditional and other rule-governed behavior; c. homo eroticus as an embodiment of emotional and expressive action; d. homo politicus epitomizing the pursuit of power and domination; e. homo honorus as an exemplar of status seeking; f. homo instituted dominated by institutionalized motivations and actions, etc.

These arguments can be11 strengthened by stressing the important difference between formal or functional and substantive or social rationality, as made by Mannheim in his Ideology and Utopia and by Weber in (Economy and Society) before. More precisely, following Weber Mannheim (1936:114, n.3) distinguishes between two types of what he calls the “rationalized sphere.” The first type is what is called a “theoretical, rational approach” based on mechanical calculation, the case in point being a technique that is “rationally calculated and determined.” Hence, this type can be considered to represent technical, functional or formal rationality in the sense of what Weber calls “quantitative speculation or accounting” that is “technically possible” and “actually applied.” The second type is called rationalization as a process in which a sequence of events features a “regular, expected (probable) course”, and which is exemplified by social norms like conventions, usages, or customs expressing certain values. As such, this type seems to represent substantive or social rationality in the Weber sense of action undertaken “under some criterion” of ultimate values. At this juncture, Mannheim in his “diagnosis of our time” detects some degree of contradiction between functional and substantive rationality in capitalist society. For example, he observes that modern economic life while “extensively rationalized on the technical side” and “calculable” to a limited degree does not represent a “planned economy” and thus substantive rationality (Mannheim 1936:115). In a similar vein, Mannheim notes the contradiction in the polity between the “formal rationalization” of political conflicts via a parliament and the lack of a substantive solution to these conflicts. Overall, he suggests that contemporary “bourgeois society” instead of substantive rationality achieves “merely” functional rationality, including an “apparent, formal intellectualization of the inherently irrational elements’ (Mannheim 1936:122).

Also, mixed general theory can be considered to represent a truly unified model of social action. The first underlying assumption of such theory is that there are no different, rational and non-rational, types of social action as in Weberian sociology, but rather a single general mode of human rational behavior, thus establishing the “unity” of the actor and conduct. By assumption, for rational choice theory, like neoclassical economics, all “human action is necessarily rational [in the sense of Weberian instrumental rationality]” (Mises 1966:19). An alternative assumption is that this single type of social action is neither invariably rational nor non-rational (as Pareto and Freud in part imply) in economic terms, but combines in various proportions a variety of rational and non-rational elements (as Parsons contends). Simply, human action is unified but complex, i.e. both rational and non-rational. In Weber’s terms, there are no four types of action, but all action blends in different combinations components or aspects of zweckrational as well as wertrational, traditional and emotional behavior. In the terms of Pareto, there are no two separate modes of action, one in the economy (rational) and another in society (non-rational), but all behavior combines logico-rational and non-logical elements. The second assumption thus contrasts with those implied in general rational as well as non-rational theories, viz. that action is either rational or non-rational. Hence, mixed general theory is premised upon the concept of homo complexicus conceived as constituted by homo economicus and homo sociologicus, e.g. homo moralis, homo religiousus, homo politicus, homo honoris, etc. It incorporates and tries to integrate all these “hominess’ (Schumpeter 1991:337), though it may be difficult to achieve multidimensional integration (Rambo 1999). Thus understood, a mixed conception as the strategy for explanatory theory construction can be defended and preferred on these grounds: (a) promoting theoretical pluralism rather than monism; (b) providing realistic explanation as opposed to implausible simplifications, e.g. the folk psychology of homo economicus (Somers 1998), actors as Robinson Crusoes (Conlisk 1996) and/or engineers (Stiglitz 2002); (c) expressing real-life complexity “against parsimony” (Hirschman 1984); and (d) increasing substantive knowledge instead of indulging into sterile formalism.

The aforesaid of rational choice has applied mostly its hard-core, thin, or narrow model in the sense of an economic-instrumental conception of and approach to social life. One may wonder if soft, thick, and broader models of rational choice are more satisfactory than their counterparts.

At this juncture, note that some sociologists (Hechter and Kanazawa 1997) seem to think that thick rational choice theories are to be preferred, by virtue of their ability to ex ante specify concrete, mostly economic-instrumental, ends or motivations of action, to their thin counterparts that are agnostic or mute about these ends. Yet, this preference does not seem to obviate the prevalent economic thrust of thick rational choice conceptions thus understood (Friedman 1996), as exemplified in their instrumental conception of rational behavior and its corollary of teleological mis-specification. For most advocates of sociological rational choice theory or rational action theory for sociology (Goldthorpe 1998) try to distinguish their theory from its economics versions, especially the hard-core economic approach to human behavior. In passing, the above preference for thick rational choice conceptions also implies a curious or partial interpretation of thick-thin rational choice theories on the basis of whether these engage either in an explicit a priori specification of human ends or practice agnosticism or muteness in this regard.

However, rational choice theories can also be divided into thick or thin depending on whether they assume hard, extrinsic, economic-instrumental as first-order ends and motives or soft, intrinsic, non-economic ones as second-order respectively (Elster 1989:34-5). Those theories assuming the first class of ends are thin, hard or first-order, and those positing the second class, thick, soft or second order. Thus both thick and thin rational choice theories would ex ante specify engines for action. To that extent, both are not agnostic about these engines, contrary to what is expected of thin theories, particularly their formal-axiomatic versions in social choice theory predicated on consistency, especially transitivity12 , as well as neoclassical economics’ conception of human action as “necessarily rational” (see above). Hence, an additional criterion for classifying rational choice theories into thick and thin is the character of their teleological specification, viz., thick or thin description of actor ends or motives, rather than whether they perform such specification or not, thus being agnostic or non-agnostic in this regard. On the account of their thick description of actor ends, thick rational choice theories would appear preferable to their thin alternatives characterized by teleological mis-specification given the actual multiplexity (Arrow 1997:765) or thickness of these end, as discussed in more detail below.

As hinted earlier, a main problem with hard-core or thin conceptions of rational behavior is their lack of empirically valid and theoretically sound explanations of both individual agency (for recent reviews of the concept, cf., Emirbayer and Mische 1998; Kiser 1999) and social structure. And to that extent that these rational choice conceptions in their ex ante specification of purposes or engines of action assume only hard economic explanatory variables they even neglect the admonition coming from neoclassical economics itself, namely that “there are no economic ends, but only economic and non-economic ways of attainment of given ends’ (Robbins 1952:145). At this juncture, by virtue of such teleological mis-specification narrow rational choice conception is embroiled in a fallacy of commission.

On the other hand, thin conceptions face risks of tautology, alongside or in conjunction with their self-inflicted wound of a veil of ignorance or agnosticism as regards human ends and motives. However, such agnosticism may involve a fallacy of omission, because by being completely mute about human ends can often be a head-in-sand (Frank 1996:120), and thus not an exceedingly productive, approach. In retrospect, this teleological agnosticism closely follows cognate approaches to human action in neoclassical (especially Austrian) economics (e.g. Mises, Hayek, and Robbins), and thus shares well-known negative or positive arguments of tautology and empirical futility, e.g. non-falsifiability, made in regard to these approaches (Friedman 1996). In particular, these risks of tautology are generated by the sub-summation of all human ends and values, hard and soft (Opp 1989), intrinsic and extrinsic, under an all-encompassing mono-utility (Etzioni 1999) utility function. The question thus arises as to whether everything is really utility and thus every behavior rational, if utility maximization equals rational behavior (Margolis 1982:16-7).

In this connection, critics charge that only by a tortuous logic (Knoke 1988) can the quest for, say, status as well as power and other non-economic ends like morality (Etzioni 1999) be lumped together into a utility function, alongside seeking wealth and other economic utilities. Generally, the admitted “problem is that a great deal of individual behavior is not explicable in wealth [utility] maximization terms [and] some behavior [is] better explained as the product of status or power maximization” (Hechter 1992:217). Moreover, pursuit of status, power and other non-economic utilities can come in conflict with seeking money, wealth, profit and generally economic utility. For example, spending wealth on gaining social prestige or political power to the point of becoming economically broke, as do some of those businessmen seeking political offices at any financial cost in the USA, does not seem to generate the same kind of utility as using that wealth to make money profit, by investing it, say, in Wall-Street. Similarly, the rich altruist that gives away all the money to significant others or society thereby becoming destitute can hardly be assumed to have the same utility function or happiness as an equally wealthy egoist that does exactly the opposite, i.e., investing for private profit or, as those proverbial misers, hoarding the wealth. Now, to call the first function psychic income versus the second as money income is misleading, because these two are incommensurable variables, the first being an instance of invaluable goods (Arrow 1997) or/and emotions (Elster 1998), and these latter are often difficult, if not impossible to conceive in cost-benefit ratios, i.e., as money income. This perhaps needs to be qualified. One can argue (as a referee commented) that while measuring psychic-income concepts like happiness is not as clear as the measurement of purely economic utility, they also can be measured. Arguably, though happiness or psychic income is relative and cannot be as precisely quantified as money income, it might be to a degree and in the same way concepts like social prestige can be numerically measured. Researchers in sociology and social psychology have been measuring prestige for some time thus making this concept at least an ordinal-level variable, though it is a subjective measure based on group judgments.

In methodological terms, the concept of psychic income, besides being but a metaphor or analogy, reflects the tendency for rational choice theory to admittedly resort to ad-hockery (Akerlof 2002; Conlisk 1996) or post-hoc theory development, when the initial optimization hypothesis is falsified (Baxter 1993). The result of this tendency to add ever new supplementary hypotheses to save the theory from empirical wreckage (Miller 1997) has been transforming the original economic conception of rational behavior featuring a thin description of human purposes or teleological agnosticism into a broader conception offering a thick description of these purposes. Presumably, the latter supplements hard with soft incentives (Opp 1989), first-order self-interested with second-order dis-interested ends (Elster 1989), extrinsic with intrinsic motivation (Frey and Oberholzer-Gee 1997), i.e., money with psychic income.

However, the problem with this resort to post-hoc theory re-development, especially the ad hoc quality of utilitarian rational behavior (Mitchell 1978:168) as implied in an all-encompassing utility function, is some kind of uneasy relationship, even tense juxtaposition, of a variety of divergent human motives and purposes. For example, to the extent that such a thick rational choice conception “juxtaposes Spencerian and Durkheimian sociologies, [it] minimizes, if not negates, the irreconcilability of these two approaches [as] “self-interest” and a “greater moral code” are mutually exclusive depictions of human motives’ (Mitchell 1978:75). This also applies to the juxtaposition of money income and psychic income, as forms of self-interest and moral code, respectively. In particular, psychic income and other supplementary variables are largely treated as residual categories relative to money income and other hard incentives in social behavior. Namely, the moment that rational choice theory, especially its thick or soft variant, uses psychic income makes one wonder of whether it “merely treats [it] as a residual category of motivation to be invoked when the theory otherwise gets into trouble” (Margolis 1982:88).

No wonder some rational choice adherents, who would rather stick to thin conceptions than generate via ad-hoc hypotheses thick conceptions have complained about such ad-hocism (Barber 1993). For example, they (Coleman 1988) lament in regard to an extension of rational choice to sociology, namely social exchange theory, that one of its deficiencies is the “attempt to introduce principles in and ad hoc fashion, such as “distributive justice” or the “norm of reciprocity””. The satisfaction such as “warm glow” derived from following such norms (Jasso and Opp 1997) and other soft incentives is then being then named psychic income, social profit, and the like. Admittedly, such and similar terms, including implicit non-economic markets are misnomers and metaphors at best (Arrow 1997).

Thus, even some economists object to what they call fallacies and perversity with such market reasoning that construes all social, including academic, cultural, and political, life as market experience to be thereby subjected to some universal market test. Specifically, “at least two things are wrong with such appeals to the “market”. First, the metaphorical [non-economic] market is less responsive to the wishes of whoever the ultimate consumer may be than is the actual market in goods and services. Appealing to the metaphorical market test is a variant of the fallacy of argumentum ad populum. A second objection […] is deeper than the metaphor is defective. Since when does the market decide truth and beauty?” (Yeager 1997:161).

The above seem to hold true of psychic income in relation to genuine or money income. For psychic income simply does not add up to money income–and often vice versa– and to that extent to utility in any sensible sense. For instance, it does not seem very sensible to argue that a Kantian altruist turned destitute homeless, with a zero money income but high psychic income, is engaging in utility-optimizing behavior, just as is a Machiavellian egoist engaging in “behaviors that involve manipulating others in one’s own interest and at cost to others’ (Bowles, Gintis and Osborne, 2001), notably “self-seeking with guile” (Williamson 2000) high money income but having small psychic income. Here the former’s pursuit of psychic income, e.g., altruistic warm glow, is detrimental to that of money income, just as is the latter’s striving for money income relative to psychic income, including, alongside warm glows, leisure. As egoist’s utility or money income seems of a qualitative different kind that of the altruist or psychic income, it is highly questionable to subsume under the same category, i.e., utility optimization, even satisficing, what are essentially different types of behavior, such as egoism and altruism, status and wealth, political power and profit, and the like. In addition, these types of income are quantitatively incomparable and incommensurable, because unlike money income psychic income cannot be measured or quantified, unless one engages in measurements, as Hayek states, of the “same logical type as Plato’s determination that a just ruler is 729 times as happy as an unjust one.”

In general, the same can be said of the measurement of utility as some over-arching happiness or fitness function of political rulers as well as of their servants, including courtiers and individual citizens. And this applies not only to the cardinal measurement of utility mostly abandoned even in mainstream economics, except perhaps game theory, but also to the ordinal, as there is no way to determine that a social agent’s utility or happiness is higher, no matter how much in numerals, than that of the other. It is thus largely impossible to say even if social agents experience just more or less utility or happiness than others, which suggests that both cardinal and ordinal interpersonal utility comparisons are here futile. Thus, the problem is not only that one cannot determined that a social agent is 729 times happier than someone else, but that one cannot even plausibly state that one is just happier, i.e., has a higher utility, than the other.

Then, there are, using economic terminology, opportunity costs, namely foregone alternatives or trade-off involved in seeking these different goals in social behavior, e.g., the more money income, material utility or self-interest, the less psychic income or altruistic warm glow, and thus the more economic disutility. A point is case is the familiar trade-off relationship between hard work, including wealth acquisition or making money, and leisure as a form of psychic income, as classically analyzed by Veblen (in his Theory of the Leisure Class), who also stressed the divergence between the use-value or utility or the instrumentality of goods and their status-value or ceremonial aspects (Ackerman 1997:653). Hence, say that in all these cases agents maximize or satisfice with respect to utility glosses over these complex relations between what is utility in economic terms, e.g., money income, and what is not, viz. status, power, leisure, and other forms of psychic income and non-economic utility overall or economic dis- and non-utility. For all these latter phenomena are in essence non-economic deviations or departures (Rabin 1998) from, rather than emanations or realizations of, utility, profit (net income) and other economic maximands, viz., utility-maximization in consumer behavior, as well as profit-maximization in producer activities. In Weber’s terms, the former represent mostly ideal, non-instrumental values, which cannot without theoretical impunity be dissolved into material interest or utility.

The above exposes the fallacy involved in thinking of these values in terms of such interests (Elster 1998), with psychic income being an instance of this reasoning, for psychological, ideal and other cultural phenomena are simply not what economists term income, profit, capital, and the like. In this sense, the term psychic income appears as an oxymoron reflecting the above fallacy, or at best an easy analogy and mere metaphor; this mutatis mutandis applies to similar pseudo-economic terms, including political profit, income, capital, exchange, or markets, etc. Moreover, as psychological and other studies report, such expressions of psychic income as “equity, fairness, status-seeking and other departures from self-interest [individual utility] are important in behavior” (Rabin 1998:16)

On the one hand, the hard, thin-rational or profit maximizing solution to the problem of motivation in social behavior, including politics, has been more or less “discredited [for] more sophisticated answers (influence on public policy, power, or simply utility)” (Wintrobe 1997:429), i.e., for a thick-rational alternative. On the other hand, the thick alternative often runs into definite problems of its own, especially pitfalls of tautology, as admonished by some advocates of the economic approach to society, including politics (Buchanan and Tullock 1962; Downs 1957; cf., also Miller 1997). As critics also object, putting everything in an all inclusive mono-utility function (Etzioni 1999) makes utility a “mere mathematical trick drained of any substantive content” (Margolis 1982:16).

Thereby, rational choice becomes by design a theory emptied by almost any substance (Popper 1967), in which the concept of rational behavior (= consistency) has “no real content” (Sugden 1991:751). The result is an unfalsifiable tautology13 that “says little about human behavior [save] that it is always and everywhere rational” (Friedman 1996:23). This applies to those thin (agnostic) rational choice conceptions in economics arguing that when “applied to the ultimate ends of action, the terms rational and irrational are inappropriate and meaningless’ (Mises 1966:19). So does it apply to thicker sociological rational choice theory (Hechter and Kanazawa 1997) maintaining that nonrational or irrational behavior “is merely so because the observers have not discovered the point of view of the actor, from which the actions is rational” (Coleman 1990:19). For maximization of utility, whatever this may be and whatever it might include, is considered an epitome of rational behavior, moreover an axiom beyond any doubts, almost the Church of England preventing and sanctioning any “deviation into impiety” (Keynes 1972:276-7). This is so, at least within the prevalent economic-instrumental conception of rational behavior and all purposeful action as an ostensibly universal and accurate calculation of utility optimization (Stigler and Becker 1977). For this conception mutates into a “mathematical deconstruction: pick a behavior and tell a story about what it might be maximizing” (Ackerman 1997:662).

Hence, while trying to make it beyond criticism, various evolutions, variations and extensions within rational choice theory can also be used as elements of its critique, however. For such attempts at extending and often changing beyond recognition an initially narrow and thin rational choice conception of society into a broader and thick one imply admitting the conception’s inadequacies. In methodological terms, since such endeavors involve ad- or post- hoc theory development (Conlisk 1996), they run the risk of ad-hockery or/and tautology, as various ad-hoc hypotheses are advanced when the initial premise of optimization fails (Baxter 1993). No wonder, many authors have asked the question if—just as others have engaged in its defense arguing that–it is futile to even criticize rational choice theory, given its transformation into an what Popper with a dose of “pride and joy” terms an ‘almost empty principle’ or unfalsifiable tautology (Friedman 1996).

This holds true above all of the axiom of universal utility optimization, in which the utility function contains virtually every possible human motive and purpose, for a tautology or self-evident axiom, like mathematical propositions (e.g., 4 x 6 = 6 x 4), cannot by definition be empirically invalidated. Thus, some economists and rational choice theorists consider this tautological property of un-testability a major advantage of their theory arguing that “there is no need for direct tests of the fundamental postulates in physics […] or in economics– the laws of maximizing utility and profit” (Machlup 1963:167).

More generally, as hinted above, some early exercises (e.g. Mises, Hayek) in a thin or agnostic rational choice conception within economics are based on the assumption that social behavior is invariably rational, thus equating human with rational action. The same assumption is found in the comprehensive economic approach to human behavior insofar as it treats non-rational behaviors and variables, including tastes, emotions and even addictions, as but subsets or mutations of the rational, i.e., of cost-benefit calculi (Becker 1991).

A case in point is the economic approach’s status of altruistic behavior as but an inverted form of rational egoism, and thus of pure altruists as sorts of free-riders (Elster 1989; Rose-Ackerman 1996) in turn variations of “rational fools’ (Sen 1977). In another case, the economic approach treats even lifelong and harmful addictions as rational choices reflecting the addict’s high-powered inter-temporal optimizing abilities rather than, as critics (Ackerman 1997:662) object, changes in tastes and otherwise non-rational processes and behaviors. The assumed equation of human and rational or instrumental action is also implied in sociological rational choice theory’s thin depiction of all social life as universal utility-optimization, though this depiction is usually agnostic regarding the content of this utility function.

As noted earlier, rational choice theory, including its public choice type, therefore has a tendency to evolve into the theory of all social life that seeks to explain virtually every phenomenon in society. The theory thereby claims to represent a “universal theoretical framework concerning rational choice and behavior” (Hodgson 1998:168). In epistemological terms, especially on account of scope-specification and definiteness, thick or soft rational choice theory in sociology can be deemed even more questionable than its thin or hard counterparts in economics. The latter are at least consistent and with a definite domain. However, they are usually unrealistic assuming away the real world (for a wide range of situations, cf., Frey and Oberholzer-Gee 1997). This assuming away of the world can14 be another explicit “point of attack” on (thin) rational choice theory, as its many critics object (cf. Archer and Tritter 2000).

On the other hand, the former as a putative a cure-all (Collins 1986) theory is internally inconsistent and even contradictory–as everything people do is rational–with indefinite/infinite scope, thus becoming simply trivial or circular. And by virtue of its tautological character, i.e., its utilitarian alchemy that dissolves everything into utility, thick rational choice theory is in danger of becoming largely useless for empirical research as well as for theory building. This danger sheds, in retrospect, light on early rational or public choice theorists’ (Buchanan 1991) warnings against the danger of tautology implied in too a broad or thick rational choice theory, especially a comprehensive utility function lumping together all human ends, as well as on the proposed resolution by confining to pseudo-economic goals (Miller 1997). It also highlights those arguments for the impossibility or futility of criticizing the marginalist utility-optimization assumption or “law” (Machlup 1963), and so rational choice theory as based on this hypothesis.

At any rate, rational choice theory seems to find itself between the Scylla of thin conceptions’ empirical unrealism and the Charybdis of thick theories’ non-falsifiable tautology assuming universal rational behavior. The former threaten to make the theory irrelevant for understanding and explaining real-life social actors and behaviors, the second to spell the end of it as we know, i.e., an economic paradigm of society, by transforming it into a circular universalistic theory.

Further, some internal contradictions in rational choice theory can also help answer the question as to whether thick or soft models are more or less adequate than their thin or hard counterparts. All these contradictions involve an initial equation of rational behavior with utility optimization, and then subsequent or ad-hoc implicit denials of this very equation. For example, the law of demand is considered to imply consumer utility optimization and thus an exemplar of rational behavior. Hence, such reversals of the law of demand as the Veblen paradox of status-driven consumption are deemed instances of irrational behavior—i.e. not utility optimizing–in hard or thin models. However, in thick or soft models these very reversals involve some sort of utility maximization or satisficing and thus rational behavior, for all action ends, including social status, are included in an over-arching utility function. Thus, utility optimization such as status or power seeking involved in such reversals of economic laws is deemed rational behavior in thick models, and non-rational one in thin models! In the case of the law of demand, utility maximization reflects rational behavior, in that of the Veblen paradox, non-rational behavior!

A next contradiction also entails equating utility optimization with rational behavior, and yet subsequently denying this very equation. First, utility maximizing behavior specifically involves maximization of money income or profit as a putative exemplar of economic rationality. Hence, in thin models the reversal of profit maximization in the form of seeking non-economic ends, e.g. psychic income, can reduce money income and thus be irrational in economic terms. However, since thick models incorporate all incentives, including psychic income as a metaphor for anything not expressive in money terms, in the utility function, optimizing or satisficing in respect to non-monetary objectives would also be rational given the equation of rational behavior with “generalized” utility maximizing behavior. Again, in one case, namely profit seeking, utility maximization is deemed rational, and in the other, pursuing extra-monetary goals, non-rational!

Still another contradiction, positing and negating equation between utility optimization and rational behavior, is implied in the rational choice treatment of egoism and altruism. On the one hand, in rational choice theory maximizing self-interest or egoistic ends generally characterizes rational behavior by entailing utility optimization—this behavior is hence termed rational egoism (Hechter and Kanazawa 1997). Alternatively, pursuing disinterested or altruistic goals is usually seen as reflecting non-rational behavior, thus representing some sort of irrational altruism. Yet, some thick rational choice models implicitly assume that altruism like egoism can involve utility optimization, as such models include both egoistic and altruistic motivations in an all-embracing utility function. Nevertheless, rational choice theory typically links egoism with rational behavior, and altruism with non-rational behavior. The above implies a paradoxical proposition in rational choice theory: altruistic behavior can be utility optimizing in thick models but not rational in their thin versions. And this is a déjà vu contradiction: in one occasion like egoism, rational choice theory equates rational behavior with utility maximization, in another one, that is altruism, not.

In the preceding I have detected and discussed the peculiar conception of rational behavior in what is putatively rational choice theory in both economics and sociology, and advanced a corrective in the form of a broader definition and conceptualization of rational behavior as both instrumental, economic or individual and non-instrumental, extra-economic or social. This discussion has indicated the existence and proliferation of various methodological and conceptual anomalies, paradoxes or pathologies (Smelser 1992) that the comprehensive and often indiscriminate extension of the instrumental conception of rational behavior, as established in neoclassical economics–as a hallmark of current rational choice theory, engenders in sociology and related social science disciplines. For example, the questionable expansions of the neoclassical theory of economic, including consumer, rationality as utility maximization into other fields only further expose what is deeply wrong with this theory in the first place (Ackerman 1997:652).

Also, the discussion suggests ways for analytically remedying such pathologies of rational choice theory that make the latter appear, like its neoclassical economic progenitor, “primitive” suffering from “ad hockery,” even “blind and foolish” (Akerlof 2002), “positively bizarre” (Margolis 1982), a “little bit silly” (Etzioni 1999), at best “one side of the coin” (Arrow 1990) or just “amusing” (Friedland and Robertson 1990). In general, most of these pathologies seem to ensue from an inability to understand and explain the complexities of human life in society (Sen 1990), including the complex nature and workings of rational behavior itself.

All of this casts serious doubts on the explanatory viability of rational choice theory as a designated paradigmatic exemplar for all social science, including sociology and political science, alongside economics. Admittedly, in its current versions rational choice theory is “not a general [social] theory because it uses a much too rigid and narrow conception of rationality”15 (Boudon 1998:821), as attempted to show in the preceding. This narrow conception grossly neglects both the logical possibility and the empirical evidence that human behavior can be rational not just on economic criteria but also on extra-economic ones. Neglected is thus the incidence and salience of non-economic rationality in favor of its economic form. That rational behavior exhibits both economical and non-economic rationality can be deemed the key argument and inference of this paper. Hence, the foregoing suggests that human behavior can be not only economically rational but also non-rational in economic terms and yet rational in non-economic ones.

Finally, the question may arise as to what is the difference between the conception of rational behavior advanced here and sociological rational action theory, because it would seem that their common trait is that both represent broader alternatives to the economic-instrumental conception of rational behavior. First, the conception of rational behavior in this paper ex ante specifies ends of social action, while thin sociological rational choice theory tends to be agnostic (Goldthorpe 1998) or mute (Hechter and Kanazawa 1997) about these ends and thus involves fallacy of omission. Second, the conception outlined in this paper does not treat economic ends as necessarily more fundamental than the non-economic; on the contrary the former are often just means or intermediate objectives to the latter as ultimate goals. In contrast, both thin and thick sociological rational choice theories treat economic ends as being of a first-order in relation to the non-economic ones as being of a second-order, and thus evince a high degree of economic reductionism. Third, the present conception makes a clear distinction between instrumental and other, non-instrumental ends of social action so that not all human goals and motives are subsumed under an all-embracing utility function as in thin sociological rational choice theory, which is therefore as plagued by an instrumental bias as its economic counterpart. A further elaboration of these differences between these two conceptions of rational choice can be, however, a content of another paper.

Abell, P. (2000). Putting Social Theory Right? Sociological Theory 18, 518-523.

Ackerman, F. (1997). Consumed in Theory: Alternative Perspectives on the Economics of Consumption. Journal of Economic Issues, xxxi, 651-664.

Akerlof, G. (2002). Behavioral Macroeconomics and Macroeconomic Behavior. American Economic Review 92, 411-433.

Alexander, J. (1990). Structure, Value, Action. American Sociological Review 55, 339-345.

Archer, M. and J. Tritter (eds.). 2000. Rational Choice Theory. London: Routledge.

Arrow, K. (1990). Economics and Sociology. In R. Swedberg (Ed.), Economics and Sociology (pp. 136-148). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Arrow, K. (1994). Methodological Individualism And Social Knowledge. American Economic Review 84, 1-9.

Arrow, K. (1997). Invaluable Goods. Journal of Economic Literature 35, 757-765.

Barber, B. (1993). Constructing the Social System. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.

Baxter, J. (1993). Behavioral Foundations of Economics. London: St. Martin’s Press.

Becker, G. (1976). The Economic Approach to Human Behavior. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Becker, G. (1991). A Treatise on the Family. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Becker, G. and K. Murphy. (2000) Social Economics. Harvard: Harvard University Press.

Bonham, J. (1992). The Limits of Rational Choice Explanation. In J. Coleman, and T. Fararo (Eds.), Rational Choice Theory (pp. 208-227). Newbury Park: SAGE Publications.

Boudon, R. (1981). The Logic of Social Action. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Boudon, R. (1982). The Unintended Consequences of Social Action. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Boudon, R. (1989). Subjective Rationality and the Explanation of Social Behavior. Rationality and Society 1, 173-196.

Boudon, R. (1996). The `Cognitivist Model”. Rationality & Society 8, 123-151.

Boudon, R. (1998). Limitations of Rational Choice Theory. American Journal of Sociology 104, 817-826.

Bourdieu, P. (1988). Outline of a Theory of Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bowles, S. (1998). Endogenous Preferences: The Cultural Consequences Of Markets And Other Economic Institutions. Journal of Economic Literature, 36, 75-111.

Bowles S., H. Gintis and M. Osborne. (2001). The Determinants of Earnings: A Behavioral Approach. Journal of Economic Literature 39, 1137-1176.

Buchanan, J. (1991). Constitutional Economics. London: Basil Blackwell.

Coleman, J. (1986). Individual Interests and Collective Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Coleman, J. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology, 94, S95-120.