Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Amin Alhassan

This paper is interrogates contemporary communication policy practices of the Ghanaian state. The rise of the global digital economy has transformed the hitherto bland telecommunication sector in developing countries into a steamy and juicy pie that attracts the attention of big business, the expertise and finance of international capital, as well as local businesses. In its bid to increase phone access, the postcolonial state in Ghana, under the tutelage of organizations such as the World Bank, has embarked on setting in place a new regime of liberalized and privatized telecom industry. A new regulatory agency, National Communication Authority has been put in place to independently oversee the sector. But can the state and its purportedly independent regulator face up to the challenges and the temptations of the new digital economy? What are the motives of the policy choices made? What are the forces that shape policy trajectory? These are some of the questions discussed in this article as it tells the story of the vagaries of policy action in the apparently indomitable new world of telecom politics in Ghana.

The experience in Latin America confirms that privatizing the telecommunication industry does not always translate to increased access (Winseck 2002, 26, Melody 1999, 14). It is also the case that for reasons of national sovereignty many African and Arab countries are reluctant to privatize totally. National telecom networks in developing countries are generally seen as symbols of national pride. These observations hold true for Ghana both in the parliamentary debates about the law that deregulated telecom and the government’s timid efforts to implement it. The fear of alienating the people and making them feel a sense of national loss may have accounted for why Ghana did not totally privatize, but rather opted for a regulated sector with controlled private sector participation. During the debates in 1994, a member of parliament posed a caution to the House that Ghana Telecom (GT) “is a symbol of national sovereignty and that any communication policy should aim at protecting it.”1 According to Winseck (2002, 26), the general unwillingness to privatize completely suggests that the global dogma of deregulation in the 1980s and 1990s is being reversed.

The emerging consensus is that “strong governance regimes are vital pillars of telecommunications policy reform.” But is the postcolonial state capable of setting up an effective regulatory mechanism? This article examines Ghana’s telecom privatization experience, particularly its efforts setting up the National Communications Authority (NCA) as the national regulator to oversee a duopolistic telecom sector. What does it mean for a downsized state and its institutions such as NCA to regulate big business in an emerging telecom sector? Is the postcolonial state up to the task of instituting a strong governance regime over the steamy and juicy sector of telecommunications in a flourishing era of digital capitalism? This paper will try to interrogate the policy practices of the state in the telecom sector in Ghana and look at some of the sources of pressures on the state, that make the possibility of a strong telecom governance regime remain a phantom.

The NCA was established by an Act of Parliament, the NCA Act 524, 1996, as part of Ghana’s telecom sector reform policy implemented in 1996 to introduce privatization, liberalization, and controlled competition into the telecommunications industry. This effort corresponds to a global push for separate national regulatory bodies different from the regular ministries or departments of state. In 1990, there were only 12 of such bodies in the world. And by 1996 NCA became one of 53 in the world. The figure rose to 101 by 2000 (ITU 2001).

Ghana’s NCA has the regulatory responsibility of ensuring a level playing field in the industry and the attainment of public policy goals in communications. Specifically, its functions include the regulation of communications by wire, cable, radio, television, satellite, and other related technologies in Ghana. According to Samarajiva (2001), national regulatory agencies such as NCA emerged as part of the global demand for the creation of independent, non-arbitrary and consistent decision-making agencies to guarantee stable environment for long-term investment in the telecom sector.

The NCA act defines the responsibilities of this regulatory body as: (i) setting technical standards; (ii) licensing service providers; (iii) providing guidelines on tariffs chargeable for services; (iv) monitoring the quality of service providers and initiate corrective action where necessary; (v) setting terms and guidelines for interconnections of the different networks; (vi) considering complaints from telecom users and taking corrective action where necessary; (vii) controlling the assignment and use of the radio frequency spectrum; (viii) resolving disputes between service providers and between service providers and customers; (ix) controlling the national numbering plan; (x) controlling the importation and use of types of communication equipment; and last but not the least, (xii) advising the minister of communications on policy formulation and development strategies of the communications industry.2 Until the formation of the NCA, the Frequency Registration and Control Board (FRCB) administered the electro-magnetic spectrum. Before the creation of the NCA, Ghana Posts and Telecommunications Corporation (P&T) controlled matters related to telecommunication services. The NCA act abolished the FRCB and put the new body in charge of regulating the industry. Administratively, the NCA has four directorates—Frequency Management, Regulation and Licensing, Legal, and Finance and Administration—with a director-general as the overseer. In the absence of a board of directors, the director- general reports to the minister of communications. In all respects, the NCA act has all the trappings of power that parliament found it fit to endow a sensitive organization such as the national communication regulator. In formulating the bill, the government frequently referred to the FCC in the USA, CRTC in Canada, and Oftel in the UK as its models.

A look at the trajectory of how the bill became law suggests that the parliamentary process was tortuous. The bill made its first appearance in parliament on November 15, 1994,3 and for the next two years it moved in and out of parliament, first passed by the House and then vetoed by the president. A revised bill was re-introduced into parliament and passed into law two years after it was first drafted. Besides the president’s veto, a Supreme Court case about the legal status of a radio station broadcasting on an unregistered frequency also delayed the 1996 re-introduction of the bill. This case arose because a regulatory vacuum emerged in the time spanning the adoption of the 1992 constitution and the passing of the NCA bill into law. The freedom of media provision in the 1992 constitution says: “There shall be no impediments to the establishment of private press or media; and in particular, there shall be no law requiring any person to obtain a license as a prerequisite to the establishment or operation of a newspaper, journal or other media for mass communication or information” (Constitution of Ghana, Chapter 12, article162 Sect. 3). Some legal scholars argued that this article authorizes the operation of a radio station and makes no provision for licensing at all. Working with this interpretation, a new private broadcasting station, Radio Eye, run by Independent Media Corporation of Ghana (IMCG) started broadcasting without seeking government approval. The police traced the location of the transmitters and confiscated them. The IMCG then took the matter to the Supreme Court. Thus when the government was ready to re-introduce the bill to parliament in 1996, it had to wait until the Supreme Court decided the case. There was a theoretical possibility, government believed, that the Supreme Court interpretation of the constitution could void sections of the draft bill, if they are found to be in conflict with the constitution. Fortunately for the government, the July 23 1996 ruling of the court upheld the government’s right to regulate the radio spectrum, if the intention is to ensure sanity on the airwaves and not to control either speech or the media. The Supreme Court based its ruling on the constitutional clause that recognized government’s right to make “laws that are reasonably required in the interest of national security, public order, public morality and for the purpose of protecting the reputations, rights and freedoms of other persons” (Chapter 12, article 164).

A very notable feature of the procedures that produced the NCA law was the level of contribution of industry stakeholders outside government. Parliament solicited the opinion of organizations that were going to be structurally affected by the bill. These include Posts and Telecommunications Corporation, which was going to be split into two; the Ghana Broadcasting Corporation, which was going to lose its unchecked freedom over the choice of frequencies to broadcast; the National Frequency Registration and Control Board (NFRCB), which was going to be dissolved; and the National Media Commission, which was assumed would take over broadcasting frequencies regulation. All these organizations made representations before the Parliamentary Committee on Transport and Communications. Millicom Ghana Ltd., a local subsidiary of Millicom Cellular International (MCI), then the only provider of mobile telephone services in the country, also submitted a memorandum.

On the side of civil society, the School of Communication Studies of the University of Ghana, the Ghana Journalists Association, Private Newspaper Publishers Associations, and Independent Media Corporation of Ghana (IMCG) all made representations. (IMCG—now defunct—was then seen as a national advocate of media freedom, following its testing of the limits of the law by taking the police to the Supreme Court.) Dr. B.D.K. Henaku of the University of Leiden Institute of Law and Mr. Ohene Ntow, a local journalist, made individual submissions. Going by the country’s previous experience, this wide array of input from state and organized civil society is rather comprehensive. That the government sought the opinion of the civil society signals the importance of telecom, broadcasting, and communication issues in general to the national imagination.

When the bill made its second trip to the parliament, it was swiftly passed in 1996. However, no Board of Directors was constituted until December 2000, one week to NDC government’s relinquishing of power after its defeat in the general elections. The outgoing minister of communications, John Mahama, appointed himself chairman of the board and swore other members into office. An Accra newspaper described the action of the outgoing minister in the following terms: “One of the most bizarre moves by the departing government of the NDC was the last minute appointment it made to the National Communication Authority (NCA). It was a highly suspicious move that was so audacious in its brazenness that, the NDC could only have taken such a decision to cover up some misdeeds.”4 But more worrisome was the fact that the NCA was made to operate for four years without a board of directors and only with an acting director-general. It has been virtually impossible to find out to what extent the NCA’s expected position as an independent regulator was compromised because of the lack of a transparent regime of operations. But given a scenario of an absent board of directors, which is expected to approve decisions of the director-general, and also the absence of a substantive director-general, it stands to reason that the NCA operated more or less as an extension of the ministry of ommunications.

Once the new NPP government assumed office, one of its first policy decisions was to reconstitute the board. But then again, in a ridiculous turn of events, it appointed the new minister of communication as temporary board chairman. The minister occupied that “temporary” position for more than a year. Various actors in the telecom sector questioned the appointment of a government minister as board chairman of a supposedly independent regulatory agency. Samarajiva (2001, 2) has observed that in many developing countries, governments are wary of losing control of what they consider to be legitimate government business to newly formed independent regulatory agencies. The situation in Ghana closely resembles the Sri Lankan experience between 1991 and 1996when, as reported by Samarajiva, government showed little enthusiasm for the independence of the telecom regulatory agency in spite of the well thought out legislation that authorized the body.

Ghana’s NCA act clearly specifies that it is only when there is no board of directors that the director-general reports to the minister and that the only regular relationship between the ministry of communications and the NCA is an advisory one on matters about policy. No one has taken the step so far to go to court to question the legality of a minister of communications doubling as the NCA board chairman, although a local IT specialist, Dr. Amos Anyimadu remains a consistent critic of the minister’s appointment. In a newspaper interview, he dismissed the minister’s explanation that it is regular practice in countries such as Morocco that the sector minister presides over the board: “He should resign. It is doing a great damage. I have read his explanation very closely . . . The big question they are going to ask is whether the regulatory organ is independent or not. If you have a minister in the chair, then it’s going to be difficult to say that it’s independent.”5

Why was the previous government reluctant to set up a board of directors to augment the independence of the NCA and only had to do so when it was leaving office? Why is the new government reluctant to give the regulatory agency the independence it deserves by appointing a separate board chairman? By appointing the minister as chair of the board of directors, the NPP government undermines the board’s independence and gives itself control over who gets a license to broadcast, and who gets to participate in the telecom business. When the idea of setting up NCA was introduced to parliament for the first time in 1994, the then minister of transport and communications, Edward Salia, premised the need for a national regulator on the rhetoric of independence from the state: “Mr. Speaker,” the minister argued, “the National Communications Authority bill has been designed that it will offer transparency in the regulations of telecommunication services as well as in the provision of mass communications. Contrary to popular but uninformed opinion, the National Communications Authority is not supposed to be at the beck and call of any Minister. It is an independent body and for the first time it will be able to administer telecommunications as well as the broadcast sector and give individuals the opportunity even to go to court when they are dissatisfied with the behavior of the National Communications Authority.”6 If such were the founding ideas behind the setting up of the NCA, why would the state turn around and subvert the very dream of independent and strong regulator?

The lure of controlling broadcasting frequencies is a likely source of attraction for continued control of the NCA for the two governments that the country has experienced since the establishment of this body. During the first round of debates of the NCA bill in parliament, some members called for a new law that would spell out the modalities for the allocation of frequencies. But this was not the road taken. The politicization of NCA and the government’s persistent failure to honor the regulator’s independence would probably have diminished, if the process of frequency allocation were made transparent with a more comprehensive legislation as some MPs even from the side of the ruling government then suggested.7 My belief is that because the telecom sector remains the most sensitive and arguably the richest sector of the economy, (now that the gold mines have been completely privatized) the state is reluctant to give up its control of the industry. The NCA is not an issue one can easily solicit opinion on at the Ministry of Communications and Technology in Accra, as my experience there showed. However, as a very senior public servant at the ministry told me informally, government believed that the minister’s appointment to the NCA board was to help strengthen the operations of the regulatory agency. If this were truly the case, should we be looking out for a strong NCA as the telecom policeman in Ghana?

From the legal point of view, the NCA is a government initiative or, more precisely, a state initiative. After all it was the executive branch of government that introduced the enabling bill to parliament. But that would be a naive view given the fact that the entire project of telecom liberalization and privatization, is part of a comprehensive program of economic restructuring that the World Bank and IMF forced on the country—as they have done in many postcolonial states—to prevent the state from financial insolvency. (Mustafa et. al. 1997). As it will turn out, after the state bared its chest out to display a semblance of legitimacy and observance of the rule of law by sending a bill through the legislature and passing it into law, the World Bank will be the main driving force in the setting up of even the NCA. During my investigations at the NCA in Accra, I found out that even the location and the decision to acquire rented premises to house the NCA was largely taken by the office of the World Bank Country Representative in Accra.

As part of the strategies for realizing the telecom sector reform policy objectives, the market model designed for the Ghana telecom sector was a duopoly with the privatized Ghana Telecom (GT) and Westel, an American telecom company with local partners, being the two actors in the market. GT’s strategic investor was G-Com Ltd., which outbid companies like AT&T and paid 38 million US dollars for a 30% share of the 127 million dollar GT. G-Com is a consortium of four companies, with Telekom Malaysia owning 85% shares. The other three shareholders are Sulana Electric (5%), a local company, NCS (5%), another local company, and Giant International (5%). Such a composition made Telekom Malaysia synonymous with G-Com, especially in the Ghanaian media. As part of the contractual agreement between Ghana Government and G-Com, the latter had management and technical consultancy responsibility over GT. In other words, Ghana government, despite its dominant 70% ownership, gave up the management of GT to the Malaysians. Also, the government had three representatives on the board of directors and Telekom Malaysia, through G-Com, had four. At the end of 2000, two of the three Ghanaians on the board resigned without publicly giving reasons. The NDC government did not replace them and, as a result, gave the Malaysians total control of GT. This decision later haunted the NDC government during December 2000 elections.

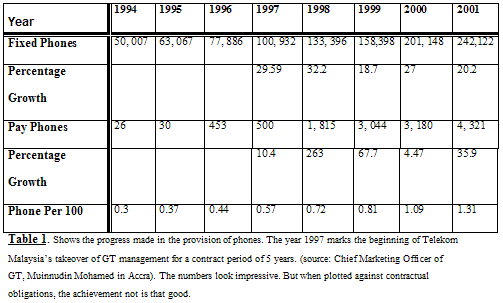

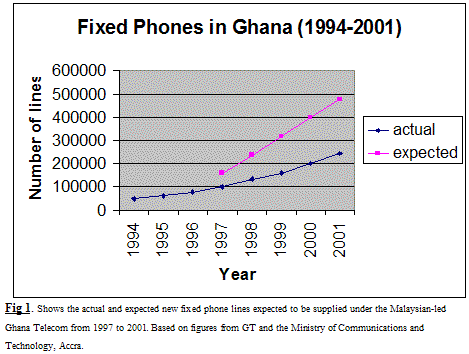

When the NPP formed the new government in January 2001, it renegotiated terms of the composition of the board of directors with the Malaysians and increased government representation to six to reflect its majority shareholding. In February 2002, on the expiration of the original contract that the previous government signed with the Malaysians, the NPP government refused to renew the contract alleging that Telekom Malaysia has not fulfilled its contractual obligation to add, by 2002, 400,000 additional lines to the 80,000 existing in 1997. The company did not provide even half of what was required. It provided 160,000 instead of the 400,000 it had promised, falling short by 240,0008 . Nonetheless, the former minister of communications, John Mahama,9 rated Telekom Malaysia’s performance impressive. The following table shows the basis of his appreciation:

Much of the intellectual foundations of Ghana’s telecom reforms can be traced to a World Bank publication (Mustafa et al 1997) on telecom reforms in sub-Sahara Africa. Indeed, Ghana’s minister of Communication and Technology, Felix Owusu Agyepong, recently admitted that his ministry simply lacks the expertise on telecom matters.10 World Bank country report for Ghana argues for the separation of “post” from “telecom” saying that when telecom stands alone, it will be better placed to attract private sector capital and management (Mustafa et al 1997, 20). The NDPC stated in its national development blueprint that: “The reform policy seeks to strengthen Ghana Telecom through the engagement of a strategic investor to bring into the company finance, infrastructure and management expertise” (Ghana-Vision 2020 1997, 176). The Ghana government document that announced the sale process also categorically indicated the attraction of foreign capital as the reason for the sale (Telecommunications in Ghana 1996). In reality, Telekom Malaysia, the “strategic investor” in GT, actually did not bring in the expected capital. The Malaysian managing director of GT, Data Abdul Mallek Mohamed was very emphatic in an interview in Accra in June 2002 that G-Com, actually a front for Telekom Malaysia, was not contractually bound to invest in GT. Meanwhile four years earlier, when the government was trumpeting World Bank recommendations for privatizing telecom, it said the strategic investor would bring in needed cash to expand Ghana’s telecom infrastructure.

Who is speaking the truth: the Malaysians or the documents announcing the sale? One may not be able to tell. But we do know that the neither G-Com nor Telekom Malaysia brought in additional financial investment into the sector apart from the share price they paid, which was received as government revenue and not financial investment for GT. It is not on record that the NDC government ever faulted the Malaysians on this score.

Moreover, G-Com’s woeful inability to meet the 400,000-line target for which it received unfettered control over management and technical consultancy over GT testifies to the failure of the experiment with private sector-led telecom policy in developing countries. In World Bank recommendations, the private sector is touted as the magic wand for the telecom problems of developing countries. But as the Ghanaian experience with G-Com and Westel, which I will discuss shortly, show, when it comes to plain old telephones (POTS) the private sector is no better than the time tested public or natural monopoly arrangement that has now come under assault.

The World Bank has an unshakeable trust in the private sector to deliver phone lines to the entire country. But in recommending the privatization of telecom in Sub-Saharan Africa, where less than 5% of the population have access, the World Bank bases its thinking on contemporary European experience. This policy:

reflects in part the consensus view that the future of telecommunications lies with private commercial provision of services under relatively liberal regulatory arrangements. In part, it also reflects the specific common aims of the telecommunications policy of the European Union (EU). Formally, the EU has focused on the gradual liberalization of international services between member states and the standardization of regulatory processes to eliminate barriers to entry at the national level. The responses by member states to this policy have tended to include plans to extend liberalization moves to domestic as well as international services and to privatize incumbent operators (Mustafa et. al. 1997, 13-14)

It is true that the European Union formally focuses on gradual liberalization, but it formerly did not. First of all what we have here is a Europe that is now using the market model after successfully using the state to put in place the basic telecom infrastructure. The World Bank experts know this but prefer to insist that Ghana and other African countries use the market model to solve their basic infrastructure problem. The history of shifting paradigms of communication regulation from heavy public service orientation to an increasing marketized sector in Europe is totally absent in the World Bank’s understanding of the European experience. Should World Bank policies reflect this history, it would mean admitting that a strong state role is needed to fund basic infrastructure first before we adopt contemporary European practice of opening to the market.

I want to raise two issues. In the first place when the telecom sector was to be privatized, both the World Bank and the government used the lure of attracting more foreign financial investors to justify selling off a portion of GT. But that expectation did not guide policy-making. It was not even considered an important factor at the handing over of GT to the Malaysians. Why did the state fail to pursue due diligence and transparency in these transactions, especially that G-Com took over GT during a particularly rosy milieu?

Without doubt, the number of phone lines increased under the G-Com regime. However, the increase is attributable more to contemporary circumstances than to the wizardry of the privatized telecom company. Cheaper digital technology made international communication more affordable, and the ever-increasing number of Ghanaians abroad produced an exponential rise in the volume of international phone calls originating and ending in Ghana. Statistics on the number of Ghanaians abroad is almost impossible to come by. But any perceptive observer in Ghana would understand that the number of Ghanaians abroad who keep regular contact with home has increased in recent years. In 1999, for instance, remittances from individuals living abroad was said to be the second major source of direct hard currency flow into the Ghanaian economy, outstripping cocoa for the first time and second only to gold exports. This development implies that a commensurate growth in international telephony was a major revenue source for GT. While it was not possible to come by historical figures on the percentage of GT’s revenue that normally come from international telephony, the fact that the figure was 68% in 1995 should give us an idea (Telecommunications in Ghana 1996, 2). With such a juicy share of the market, GT, with Westel, monopolized the sector for the five-year period as part of the terms of the contract with the Ghana government. In view of these advantages, the tendency to credit the growth in telecom services to the private sector at the corporate level appears to be an exaggeration. Furthermore, shortly before the privatization of GT, government funded a massive rehabilitation exercise that was virtually ready to take-off when the private sector took over. Thus the 160,000 new phone lines provided during the G-Com era are more properly attributable to the state’s pre-liberalization investment than the efficiency of the private sector. After liberalization, GT could fix more realistic tariffs. This it could not do when it was part Ghana of Posts and Telegraph.

When the NPP won the December 2000 elections, it made it clear that it did not like the contractual arrangement between G-Com and Ghana government. Even while in opposition, the NPP, using the rhetoric of “us” against “them,” always insisted that the arrangement was a sellout to foreigners. The NPP also argued that it was highly unusual for a shareholder to take over management with only 30 percent ownership. Thus when the first five-year exclusivity period for fixed line and international telephony was due for renewal in Febraury 2002, the NPP, now in government, abrogated the original contract.

A deputy director of administration at the ministry of communications and technology, who requests anonymity, told me the position of the NPP administration was that many aspects of the contract with the previous government had to be clarified. I also gathered that attempts to renegotiate the contract and recompose the board to reflect the company’s ownership structure found an uncooperative G-Com. The renegotiation would also have covered mechanisms for measuring performance, capital injection, and a review of the status of other minority shareholders. Given all these difficulties, the government decided to abrogate the contract entirely and look for a new strategic partner while G-Com still maintained its 30 percent ownership. But even before the government found a new strategic investor, Telekom Malaysia announced it would sell its 25.5 percent shares of G-Com holding in GT11 . As at November 2002, the other minority partners in G-Com that add up to make the 30 percent have not publicly stated their intentions.

Official articulations of the government’s position on the original contract are often stated as resistance to the malaysianization of GT and a quest to return the company to Ghanaians. The leader of United Ghana Movement (UGM), Charles Wereko-Brobby, said: “We believe that Malaysian holding of GT is no good investment as they are still struggling to build their own economy . . . Moreover, Malaysians will not allow foreigners that advantage in their own country.”12 And he was not alone. But the effect of nationalist rhetoric is really limited. Most people understand that the telecom sector needs substantial capital input that could not be mobilized locally. The main political parties, especially NDC and NPP, seem to agree that some form of privatization would be required.

The anti-privatization group that seemed to have been interested only in questioning the whole process just because the Malaysians are on the scene soon died out when the new NPP government announced late in 2001 that GT was one of 15 state-owned businesses to be wholly privatized to raise 50 million U.S. dollars to finance development projects.13 The NPP government also invited bids for a new strategic investor into the telecom sector. Telenor, the Norwegian national operator, won. As of November 2002, details of the arrangements are yet to be finalized and made public. If NPP honors its word to sell the state’s entire holding in GT, it would be the first sub-Saharan African government to do so. Hitherto, partial privatization has been the standard practice because total privatization does not necessarily lead to increased telecom access.

What motivates the state to sell its 70 percent share in GT? According to the official argument, selling GT and other state owned enterprises would generate funds for development projects.14 But is this really the case? A World Bank/IDA/IFC Country Assessment Strategy on Ghana for the year 2000 clearly states that the government should redefine its role partly by giving up its interests in non-public goods, including the media and telecom: “The main factor behind Ghana’s relatively low marks on structural reforms, as measured by several indicators of the World Bank, in spite of its early adjustment program, is either excessive state involvement in the economy, or the consequences of that involvement” (World Bank 2000, 12). It appears selling all of GT is a result of World Bank’s demand that Ghana government should severely curtail its “involvement in the economy,” the poor performance of the private sector notwithstanding.

As part of the process of creating the duopoly in the telecom sector, the Ghana government in 1996 announced the offer for sale of a Second National Operator license (SNO license) for the provision of telecommunication services. The SNO, like GT, would provide domestic and international telecom services. These included voice telephony, leased lines, public pay phones, telegraph and telex, data, mobile and value added services. The new SNO was also going to have a 20-year initial license. During the first five years, the two carriers were to be given nationwide exclusive rights over fixed line telecom services. (Telecommunications in Ghana 1996).

One of the signs of a weak and helpless regulatory regime in the telecom industry recently emerged when President John Kufour revealed that his government did not even know the names of the shareholders of Westel, the SNO.15 Meanwhile, the NCA have stipulated the conditions under which a telecom company can be licensed to operate in Ghana. These include a mandatory dossier that contains a company profile listing evidence of incorporation and certificate to commence business, list of shareholders, technical and organizational capability, and evidence of ability to perform. When the ministry of communications announced the minimum qualifications for the prospective SNO in 1996, it added that due diligence would be done to ensure that the bidding process is transparent (Telecommunications in Ghana 1996). If what the president said is true as reported above, it means that Westel subverted the laws of Ghana on two grounds, first at the office of the Register General, where it was supposed to have registered, and then at NCA. The Register General requires that all names of founding shareholders be made known before a certificate of incorporation can be issued. Assuming Westel produced a certificate, which no one at NCA was ready to confirm to me, that means it got the license without following due process.

Events leading to President Kufour’s criticisms of Westel provide further evidence of the inability of the state and the NCA to regulate the sector. It all started when Westel failed to meet its contractual obligation of supplying 4,000 lines within five years. It could only deliver 2,000 lines and restricted its operations to Accra and Tema Metropolitan areas where businesses are concentrated. The NCA responded by slapping a 70.5 million US dollar penalty on the company. In May 2002, at the celebration of the 34 th World Telecommunications Day in Accra, the acting director-general of NCA, J.R.K. Tannoh, announced that his office will resort to a court action to compel Westel to pay, insisting that: “We are mandated to instill discipline in the telecommunications sector to ensure that customers have value for money, and any operator who does not conform to the rules will have to be sanctioned.”16 These are strong words from a regulator not known for its ability to act decisively. Westel petitioned the minister of communication for moderation, but the minister insisted that it should pay the assessed fine.

While this drama was unfolding, I sampled opinion on some selected Ghanaians known locally as IT experts. I also talked to some journalists known for reporting on IT issues in the country. The impression I gathered was that the government wanted to use that penalty as an excuse to shut down Westel and give itself the opportunity to advertise for a new SNO. “Westel is fronting for the NDC [former government] so the NPP want to disrupt it and then start all over with a new company,” said Samuel Adjei, a computer programmer passionate about government legalization of VoIP. Besides the “conspiracy theorists,” some sections of government have been calling for reverting to the old monopoly system; that is asking Westel to pack and leave the sector to GT only. One person noted for this view is senior minister and chairman of the Government Economic Management Team, Mr. J H. Mensah.

Mr. Mensah publicly expressed his wish to see AT&T become the strategic investor in a GT with a natural monopoly: “I have a friend who worked with the American AT&T for many years, he is a very senior manager. On a visit I talked to him about inviting foreign partners into telecom here. He came here himself and decided that the Ghana market AT&T was not willing…from then on he talked to me, we have communicated and he is coming back to see me very soon because they have seen new potential in the market, so you know the companies are all making calculations.”17 The minister’s “new potential in the market” refers to the termination of the GT agreement with G-Com (Telekom Malaysia).18 G-Com outbid AT&T in the initial privatization of GT five years earlier. What one quickly gathers from Mr. Mensah’s words is that telecom regulation is no longer the exclusive business of the NCA. Nor is the sector ministry solely responsible for it. But that is not all the story.

As the clouds were gathering on Westel, Ghanaians least expected that the US government would intervene in a rather hawkish manner to “discipline” the anti-global market stance of the Ghana government. At least this is how the Americans interpreted the legitimate penalty on Westel. The US assistant secretary of commerce for market access and compliance, William Henry Lash, III, visited the country ostensibly to hold trade talks with government officials and private sector operators. But he went on an Accra local FM station, rather undiplomatically, to lambaste the NPP government for its allegedly unfriendly attitude to foreign investors. Referring to the penalty on Westel, he accused the government of acting irrationally. The passion with which he attacked the government on radio made a lot of observers to conclude that Mr. Lash was purposely sent to Ghana to do some damage control for Westel.

Mr. Lash’s words shocked the government, making President Kufour to announce that he was sending a protest letter to President Bush.19 “Obviously, Mr. Lash lost his balance in talking the way he did,” President Kufour grumbled. Speaking to a U.S. diplomat, President Kufour said it is very strange for the US government to acknowledge his government’s efforts to rebuild the shattered economy, only for Mr. Lash “to come here and make very disparaging remarks about the government and people of Ghana.” He also declared: “we will not allow anybody to dictate to us on how to run our economy.”20

What is revealing about this whole telecom disciplinary measure turned a diplomatic row is that the government announced shortly after the Lash attack that the president had personally intervened to reduce the Westel penalty from 70.5 million US dollars to 28 million US dollars. Whether this presidential pardon was done before or after the Lash visit is something I could not verify. Whatever the case may be, it shows the weak status of the postcolonial state when it comes to policing big business backed by an imperializing state in the form of United States. In all this process, the World Bank, known for having opinion on every policy issue on the economy, never commented on the matter.

Kufour’s unilateral action to reduce the penalty attracted negative comments from the local Ghanaian opposition and certain sections of the media. The main opposition party, NDC, issued a statement in Accra and condemned President Kufour’s unilateral action to waive more than half of the penalty. The statement signed by the Minority Chief Whip in parliament, Doe Adjaho stated: “It will appear that a pattern of executive interference in independent and autonomous institutions is being established …The NCA has commenced the process of imposing the full penalty of 71 million UD dollars and has held a hearing on the matter at which Westel presented its case. While the process is ongoing, it will appear that the President has unilaterally negotiated a 50 million-dollar reduction of the penalty against the public interest.”21 At a public lecture organized by the Socialist Forum, a small but committed group of Marxists in Accra, Kwesi Pratt, the editor of an Accra weekly, The Insight, condemned the president’s action. Present at the Socialist Forum gathering were academics, workers, and key opposition figures, including a former presidential candidate.

From the above discussion, we see the helplessness of a weak regulatory agency, functioning within an equally helpless state, as it confronts the machinations of sophisticated transnational capital. The ambivalent and shady relationship between agents of transnational capital and the Ghanaian government is not peculiar. When Galtung discusses his communicative theory of the state, capital, and civil society, he makes an interesting observation about the relationship between capital and the state. Galtung points out that the state is occupied by individuals susceptible to the attractions and temptations of offers from capital: “Capital will always want something from the State such as permissions and contracts, and Capital will be willing to pay a ‘tip’ for the service ranging from 15% or more” (Galtung 1999, 15). What Galtung is trying to explain here is the misuse, for private profit, of the power that the state affords its actors. This interaction between capital and the state is not a novel development that is characteristic of developing countries: “As the modern state emerged from feudal social formations in Europe, the vassals and lords who became functionaries were still paid from below with products produced by the serfs, rather than from above with salaries financed from taxes paid by those who work for a living…State and Capital merged at the highest levels, setting a pattern for money flowing easily from one pocket to other” (Galtung 1999, 15).

What we can learn from Galtung’s exposition is that the abuse of public power that results from the collaboration of agents of the state and of capital has always been part of modernity. And if developing countries are experiencing it, it is because they are treading the traditional path to modernization. My project is not a research on corruption, nor am I suggesting that I have unearthed new corrupt practices in the telecom policy scene. Rather, what is obvious is the wanton lack of transparency in state conduct in matters relating to telecom business in Ghana. The lack of transparency in the policy process raises suspicion on the motivation for state actor’s choices in the entire process of privatizing GT, the licensing of operators and service providers, the setting of penalties, and the process of resolving conflicts. Galtung argues that in state/capital encounters such as we have in Ghana, the civil society loses when a key democratic requirement such as transparency is absent in decision-making: “Only with transparency can everybody concerned know what is going on and make their own inputs. Communication without transparency is also known as lobbying and is the most important channel used by capital to reach all three branches of the state: executive, legislature and, more rarely the judiciary” (Galtung 1999, 14).

The civil society has contributed to Ghana’s telecom liberalization and privatization policies. Apparently, the assumption has been that once the right laws are in place, everything else will roll out just fine. But trusting institutions to deliver within the framework of the law underrates the influence of institutions on individuals. In the Ghanaian scheme of things, the limits of institutional agency, in relation to human agency, have been demonstrated by the conduct of two ministers of communications in two different governments. Both individuals, for example, appointed themselves to the chair of the NCA board of directors and undermined the independence of that regulatory agency.

One of the issues that emerged as I talked to various civil society groups was the dearth of knowledge about the intricacies and implications of policies that the government had decided on. Even the press limited itself to routine reporting of developments in the sector without an indepth analytical focus. For instance, when G-Com, with only 30% shares, took control of GT, it raised little concern in the media. It is not that the Ghanaian press was not appalled by such an apparently fraudulent arrangement, Mr. Yaw Opoku, a lawyer and a feature writer for the Weekly Insight newspaper, told me. Rather, he said, “the press simply lacks the expertise and technical know-how on telecom regulatory issues and IT.”

What has also emerged from my discussion of regulative issues is the lack of distinction between the executive branch of government and the NCA. For the president to take a unilateral decision on an issue that is being resolved by the purportedly independent NCA does not augur well for the development of the national regulator as a strong policing agency at the periphery of the global digital economy. Writing from the experience of being a former head of Sri Lanka’s Telecom Regulatory Commission, as well as being a veteran theorist in international communication, Rohan Samarajiva (2001) notes that the relationship between the state and regulatory agencies worldwide, with the probable exception of the Nordic countries, have not been without problems of interference. He notes that President Bush’s replacing William Kennard as FCC chairman shortly after coming into office in January 2001 demonstrates that “independence has subtle nuances, even in the country that invented the concept” (Samarajiva 2001, 4).

Nonetheless, independence is fundamental to the realization of the objectives for which the new regulators in developing countries were put in place. In countries where good governance is yet to be developed as a culture of the state, the national regulator needs distance and insulation from the state’s whims. Samarajiva argues that “a firewall to keep out the virus of bad governance” is needed in such countries because bad governance has its own logic, which ultimately undermines the independence and legitimacy of the regulator. One of the most important elements of effective regulation is legitimacy beyond mere legality. This type of legitimacy is achieved when various constituents of the telecom sector accept the authority of the regulator in matters of arbitration and even opinion. When such legitimacy is lacking, telecom operators are likely to challenge the authority of regulators by appealing to the executive, as in the Westel example, or, through litigation, to the judiciary. Oftentimes, when regulator legitimacy is lacking, corruption finds its way in through the back door.

Constitution of the Republic of Ghana (1992) Accra: Assembly Press

Galtung, Johan (1999) “The State, Capital and Civil Society: a Problem of Communication” in Richard Vincent, Nordenstreng and Traber (eds.) Towards Equity in Global Communication: MacBride Update, Creskill, NJ: Hampton Press

Ghana-Vision 2020 (1997) Ghana-Vision 2020 The First Medium-Term Development Plan (1997-2000) Accra: National Development Planning Commission/Government of Ghana.

ITU (2001) Trends in Telecommunication Reform: Interconnection Regulation, Geneva: ITU

Melody, W. (1999) Telecom Reform. Telecommunications Policy 25 (pp. 7 – 34)

Mustafa, Mohammed A, Bruce Laidlaw, and Mark Brand (1997) Telecommunication Policies for Sub-Saharan Africa. A World Bank discussion paper No: 353. Washington: World Bank

Samarajiva, Rohan (2001) “Regulating in an Imperfect World: Building Independence Through Legitimacy” Telecom Regorm Vol. 1 No. 2

Winseck, Dwayne (2002) “The WTO, Emerging Policy Regimes and the Political Economy of Transnational Communications” in Marc Raboy (ed.) Global Media Policy in the New Millennium, Luton: University of Luton Press

World Bank (2000) Memorandum of the President of the International Development Association and the International Finance Corporation to the Executive Directors on a Country Assistance Strategy of the World Bank Group for the Republic of Ghana, (June 29, 2000) Report No. 20185-GH. Washington: World Bank.

1. MP for Ejura-Sekyedumasi, Peter Boakye-Ansah, Parliamentary Debates Official Reports for 12 December 1994 col. 1387.

2. The National Communications Authority Act 524 (1996), Accra: Assembly Press

3. Parliamentary Debates: Official Report for Tuesday, 15th November 1994, col. 574.

4. “Messy, Messy, Messy, NCA!” by Haruna Attah Accra Mail Vol. 2 No. 113 Febraury 15, 2001.

5. Accra Mail “Telenor Ok, But Minister Must Leave NCA Alone” 12 July 2002 available at: http://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/NewsArchive/artikel.php?ID=25592.

6. Parliamentary Debates: Official Report for Friday, 9th December 1994, col. 1294 and for Friday 25th October, 1996, col. 484.

7. The NDC MP for Ejura Sekyedumasi, Hon. Peter Boakye-Ansah was particularly forceful on this. See Parliamentary Debates: Official Report for Monday 12th December 1994, col. 1390.

8. Interview with Managing Director of GT, Dato Abdul Mallek Mohammed in Accra

9. Ghanaweb.com News Report “Minister lauds private telecom sector” (18th May 1999) available at http://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/NewsArchive/artikel.php?ID=6560.

10. “Communication Ministry Lacks Expertise – Adjepong” )13 Febraury 2002) http://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/NewsArchive/artikel.php?ID=21726

11. A Reuters business news report of 27th February, 2002

12. GNA report “ We’ll buy Ghana Telecom back – UGM” 24 October 2000

13. “Fifteen State Owned Enterprises To Be Divested” 12th September, 2001. http://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/NewsArchive/artikel.php?ID=18037

14. Ibid.

15. The President made the revelation when a deputy chief of mission at the US embassy in Accra called on him at his office on Wednesday 19th June 2002. Daily Graphic 20.June.2002 “Kufour to send protest letter to Bush”

16. “National Communication Authority threatens to sue WESTEL,” Daily Graphic, 13th May 2002

17. “T&T shows interest in Ghana Telecom,” Ghanaian Chronicle, 30th January 2002.

18. Ghanaweb.com Business News of 4th December 2001 “Malaysian Management Contract of Ghana Telecom to End Next Year.” Available at: http://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/NewsArchive/artikel.php?ID=20047

19. “National Communication Authority threatens to sue WESTEL,” Daily Graphic, 13th May 2002

20. Ibid.

21. “NDC Accuses the Executive of Arbitrary Use of Power” A Ghana News Agency Report on 25th June, 2002. The actual reduction was 42 million and not 50 million dollars as claimed by the opposition.

Copyright 2003 Africa Resource Center, Inc.